April 1, 2021

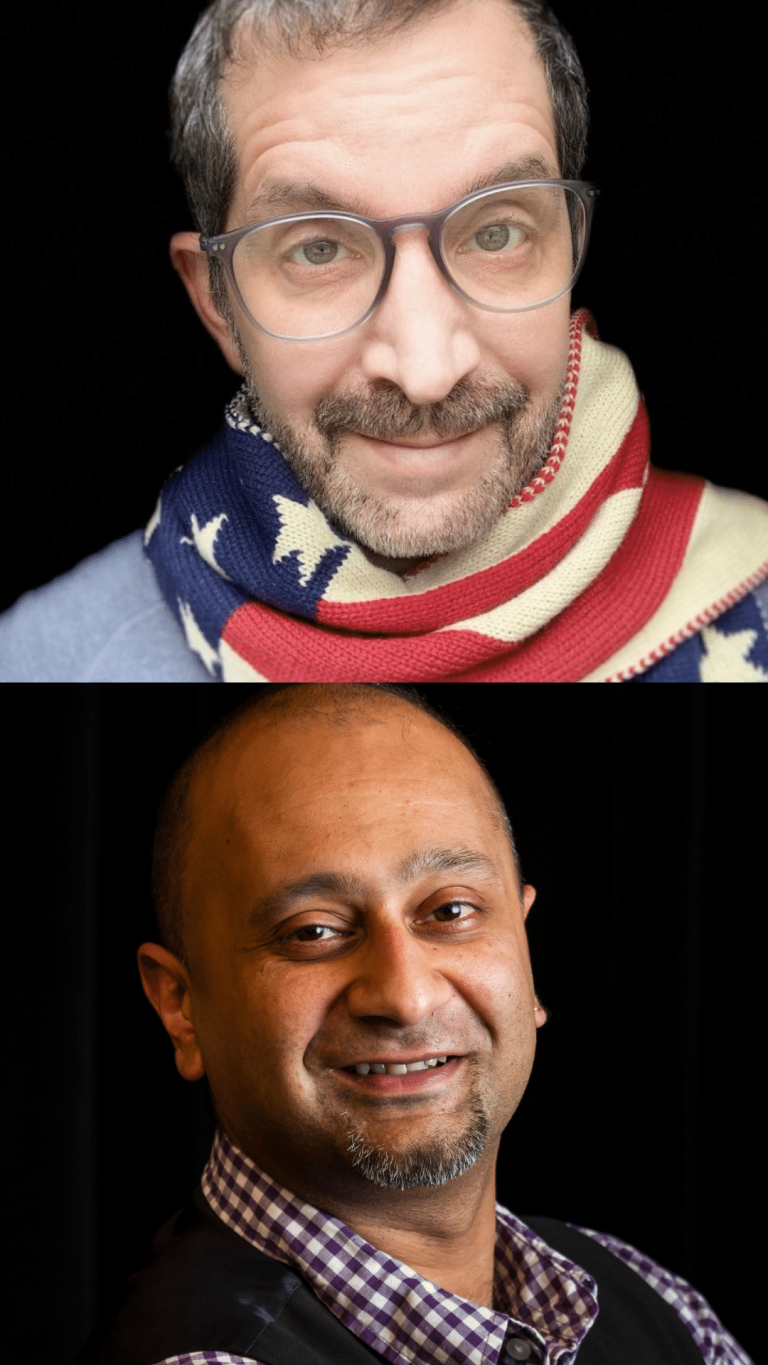

Unity and Stories with Kiran Singh Sirah and Harry Gottlieb

This special episode of Everywhere Radio features two contributors to the upcoming Rural Assembly Everywhere virtual event: Kiran Singh Sirah and Harry Gottlieb. Kiran Singh Sirah, president of the International Storytelling Center, and Whitney Kimball Coe talk about the healing power of storytelling, perfecting the practice of the “porch sit,” and Saint Dolly. Harry Gottlieb, founder of JackBox Games and a new organization called Unify America, talks with Whitney about what he believes it will take to move us from a country of politics to a country of problem-solvers. Register for Rural Assembly Everywhere, a two-day virtual festival presented by The Rural Assembly.

Transcript

Harry Gottlieb: We’re trying to fix how we make decisions. We’re trying to introduce a process that is a better process for making national decisions than what we are currently doing in Congress today.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

We all want our story to be received, to be heard, to be understood, to be appreciated, and to go into this movement. There’s something great in all of us, the story of us.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

That was Harry Gottlieb and Kiran Singh Sirah, our guests on this special edition of Everywhere Radio. In this episode, we’re highlighting these two speakers who will present at Rural Assembly Everywhere, which is taking place April 20th and 21st. You can register at ruralassembly.org/everywhere. Everywhere Radio is a production of the Rural Assembly, and I’m your host, Whitney Kimball Coe. Each episode I spotlight the good, scrappy and joyful ways rural people and their allies are building a more inclusive nation. We’re going to start this episode with Harry Gottlieb. Harry is the founder of Jellyvision and Jackbox Games, which created the popular, You Don’t Know Jack trivia game, as well as the Jackbox Party Pack, which has become very popular again this past year because of the pandemic.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Harry recently started an organization called Unify America, which brings together people from different sides of the political spectrum to work through their differences. Well, Harry, I’m really grateful to you for saying yes to joining us on Everywhere Radio. And I was trying to think back to how we got connected initially, how Unify America and Rural Assembly were connected. And I think we’re both circling around this field of bridge-building and creating networks of inclusion and coalition building that is all geared toward trying to bridge our divides and heal what’s broken in our country. And I think that’s really cool that there’s a field of work that is developing in our country that includes organizations like ours. And I think it’s really cool that Unify America and Rural Assembly have found some common purpose-

Harry Gottlieb: Have found each other.

Whitney Kimball Coe: Have we found each other? So thank you for being on this show.

Harry Gottlieb: I’m really am delighted to be on the show.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

In doing research, it sounds like you’ve actually been working on Unify America for a while now. It’s not just within this time of a real division and polarization across politics, but it started earlier than that for you. Can you describe a little bit about that?

Harry Gottlieb:

Yeah, really in the mid nineties, I was struck by the fact that if you wanted to participate in our national civic life, you had a choice of joining a fight or joining a different fight, there was no place to cooperate. You’re going to either be fighting for some issue or are you going to be fighting for a candidate, and that’s mostly still the case. Now it’s all of these years later and especially if you look at domestic issues, education, the environment, infrastructure, immigration, healthcare, I mean, the list goes on and on. We’re really stuck and we have giant problems and we have not pulled together to create giant solutions that have the support of the population. This winning by 51%, that’s not a win for anybody. That’s not a win because it’s going to be held back by the lack of support.

Harry Gottlieb:

So yeah, I launched a pilot to be like, “How can regular citizens participate and… ” Not just saying, “Okay, I’m going to join this cause or that cause, or this campaign or that campaign,” but actually first be able to examine how do we go about solving some of these problems instead of just jumping onto somebody else’s solution? How can we as a group, as Americans identify a common goal that we all have, and then look at multiple possible ways of solving for that goal. Look at the pros and cons of each and then over a series of votes, narrow it down to a most favored plan of action that actually has widespread support.

Harry Gottlieb:

But back then, it was just too early. We needed the World Wide Web, which was nine months old, so it was just like, “We’re a little ahead of ourselves.” I ended up-

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Why did you need the web? Why did you need the World Wide Web?

Harry Gottlieb:

Because to connect people in an interactive way across the country… We had very primitive chat rooms on the internet and email, there wasn’t much. So I went off and I started a couple of other software companies that have been very successful. And now I’m free again. And obviously the situation with our divisions and our inability to come together to solve problems together as citizens is… The problems are greater than ever. And it is exciting to me that there’s a whole growing movement of organizations that are all working on this.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

So you did take a break in the early stages of this Unify America type initiative and you went off and started Jackbox, or is it Jellyvision and then Jackbox, that came first?

Harry Gottlieb:

It’s complicated. It’s a tale of two companies. They’re very intermixed.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Well, I mean the first time I met you, I was a little star struck because, of course, You Don’t Know Jack and Quiplash among others are heavy favorites in our household, particularly during COVID time when virtual gaming is really the way to stay in touch with your friends and keep a sense of humor and find a little joy and find, I don’t know, some unity in this really difficult moment. And so I wonder about that time you spent designing those games, and if you had this coming together in mind, this idea of unity, did that permeate through the building of these games, or were you doing it for the fun of the work?

Harry Gottlieb:

The honest answer is that in the beginning I was encouraged to develop You Don’t Know Jack because I’d created an educational game called That’s a Fact, Jack! for middle school students. And it was seen by a friend of mine who was working in the Bay Area, who said instead of doing an educational… It was a quiz game, very similar to the format of You Don’t Know Jack where there’s a voice who’s asking the questions and you have multiple choice answers. And if you select an answer and you get it wrong, the guy gives you a little zinger, but this was for kids quizzing them on works of young adult literature. And my friend said instead of doing this as children’s education, can you do this as adult entertainment? And I mean… Okay, not that kind of adult entertainment people normally think-

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Got it.

Harry Gottlieb:

Entertainment for adults is what I meant to say. So I was not interested because I really wanted to stick with education, but he just kept bugging me. And I’m not someone who actually loves trivia games, but I thought, “Well, if you can make a trivia game funny, that could be cool.” So that’s where we ended up creating this game where the host makes fun of you if you get the wrong answers and all the questions are really weird and quirky. What was a real eye-opener, however, was when we started getting emails from people who were playing the game for whom the playing of the game was quite meaningful because it brought people together. In the early days there weren’t separate controllers, everybody was around a computer and the Q key was one buzzer and B key was another buzzer and the P key was the third buzzer and everybody’s crowded together.

Harry Gottlieb:

I mean, I can’t tell you Whitney, how many, I mean, it’s literally scores of people met their husbands and wives playing You Don’t Know Jack and then would write and tell us about it. In fact, we even helped this one guy who said, “I want to propose to my girlfriend. And we’ve played, You Don’t Know Jack through this whole process of dating and getting to know each other. Can you help us?” And so my brother, who’s the host, Tom Gottlieb, who plays the Cookie, who’s the host of You Don’t Know Jack, we created this special game that it got to a certain question, and the question was basically giving her multiple choice answers whether she wanted to marry this guy.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

I love that you bring that up because again, during this pandemic time, this has been a way my husband and I can communicate and find humor, and it’s almost like we met again, just through playing these games together. So I just think it’s very interesting that you started with a serious initiative, moved into entertainment in some ways, but still kept through with that theme of finding one another and connecting with one another. And now you have this opportunity again to go deeper. We’ll be right back after this from The Daily Yonder.

Tim Marema:

Hi, I’m Tim Marema, Editor of The Daily Yonder. Each week we publish a comprehensive report on what’s happening with COVID-19 in rural America. And we’ve got a dashboard where you can track all the information on infection, rates, cases, number of deaths and other information related to the pandemic for this and a lot more visit us at dailyyonder.com.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

I wonder if you could tell me just a little bit more about how you went from gaming again, to Unify America.

Harry Gottlieb:

There’s a few pieces to Unify America. So our mission is to replace politics with problem solving. And one of the things that we need to do first is we need to reduce contempt in this country. We are contemptuous of each other conservatives, liberals, Republicans, Democrats, et cetera.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Mm-hmm (affirmative). I think the Gottmans agree with you too. The Gottmans from the Gottman Institute say contempt is one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse.

Harry Gottlieb:

It really is.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

In our relationships, yeah.

Harry Gottlieb:

Yeah. And so it’s really an illusion because we’ve got this idea about those people who we don’t necessarily know personally. Now you can have members of your family, and that’s a much more complicated situation when you have a member of your family who has politics that you struggle with. But in general, we sort of we condemn giant swaths of the population. How could all of those people have voted that way? Those 70 plus million people, how could they have all voted that way? We have a program called the Unify Challenge it’s our first program. And we bring together people, Americans, who are different from one another. They come from different walks of life and they’re in a video conference, just the two of them. And after some icebreaker questions, they take the survey about what they think our goals should be for America.

Harry Gottlieb:

And we have paired hardcore Donald Trump fans with hardcore Bernie Sanders fans, and they are surprised by how much they agree on what America’s goals should be. I mean, in the beginning we had 50 questions and it was 46 out of 50. We are mostly fighting, now, we are mostly fighting over political personalities. You like this person, you don’t like that politician, and that law maker’s terrible, the hypocrisy here, et cetera. That’s not really moving the ball forward. The other way that we argue is over tactics. There should be a border wall; there shouldn’t be a border. There should be school vouchers; there shouldn’t be. There should be Medicare for all; there shouldn’t be. While all this is going on, we actually agree on the goals. Everyone thinks we should reduce violence, somehow. Everyone agrees that healthcare is too expensive and too many people don’t get high quality care and we should fix that.

Harry Gottlieb:

Everyone I think is aware that there are too many children who are born into situations that make it difficult for them to learn and grow all over the country. And we should be building a country where each child has the opportunity to rise to the level of their potential. Our survey, those are just three examples, but you go through lists and you look at whether it’s the environment or immigration and on and on. When you’re talking about what do you want the end state to be the final goal, we all agree. I mean, 90, 95% of Americans will agree, but we don’t see that. We don’t see that when it comes to the most important thing, which is, where do we want to eventually end up? We are deeply unified, we’re extremely unified.

Harry Gottlieb:

And so the next step is we need to now build on that to actually solve some real problems. But it requires identifying that politics is a really poor way to make decisions. And politics, which is to say, the wielding of power in order to have decisions go one way or the other, imagine pulling together 10,000 Americans from all walks of life and over a period of 18 months, trying to break down and deliberate while being educated to try to find a solution to a big national problem that we have, whether it’s healthcare or immigration or the environment or infrastructure or whatever it is. The thing that you would hope our legislators would be doing, which is working together to find a common solution, regular American citizens are capable of doing that. And there’s a lot of evidence, that’s 50 years of evidence to show that, Unify America is hoping to do that at scale at the national level.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Which is incredibly ambitious, and that’s really wonderful. But I’m also just, I’m wondering as you’re describing this, finding that common goal, first of all, if that is actually true, that when we strip away all those other things that we ultimately come to the same goal, I’m reading this book right now by Heather McGhee, it’s called, The Sum of Us. And one of her chapters is about the draining of a pool in the 1950s, 1960s in America just to keep black and brown bodies out of the pool, a community would drain a pool and keep the white kids out as well. So her thesis of course, is that this is a zero sum game that we’re playing believing that we can’t do well unless it’s at the expense of someone else.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

So coming back to the formula that you’re using with Unify America, there’s a goal, first coming to some agreement about what the ultimate goal is, and then talking about the tactics and using some sort of jury system, I guess, to work together to come up with the solutions. And then the third piece, is that what you’re describing these anti bias trainings?

Harry Gottlieb:

Yeah. So the hope is to build a community of people who are like, “We want to be problem solvers.” And say, “All right, first you need to train to be problem solvers, to be decision makers.” You need to understand your unconscious biases. You also need to know how to deliberate with people, which is, how do you listen to people so that you can really hear them? Being open-minded is a spiritual practice. We’re all open-minded sometimes the question is, can you be open-minded when someone’s really disagreeing with you and open yourself up to learning. So learning how to do that.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

And then to what end is all of this, what is the unity that we are striving for? What does it look like in real life?

Harry Gottlieb:

Well, in real life for this country to be unified, to me, it means that we have gotten rid of politics as a way of making our national decisions that we have adopted problem-solving as a way of making our national decisions. And what is problem solving? Starting with a goal, bringing people together who do not have a conflict of interest to examine the goal, examine possible solutions in depth, weigh pros and cons of each narrow it down in a consensus-building fashion until they get to a most favored plan of action. And then have a final confirmation vote that says, “Look, we can do this most favored plan of action, or we can stick with the status quo.” If you think the plan of action is so potentially problematic that we should just do nothing, then vote for nothing. Otherwise, here’s this thing that we’ve been working on for the 18 months that has risen to the top.

Harry Gottlieb:

And the hope is that in a vote like that you get 75, 80, 85% of the people say, “Let’s go with the most favorite plan of action and make this change.” And then of course, we need to work with legislators on the front end to make sure that this, all America solution to a big problem, to the extent that it requires legislation and not every problem is solved through the government. Not every problem is solved through legislation, but some part of it probably is that it actually can get implemented.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

What is the first issue or topic you’d like to wrestle with? You’d like to see this applied to?

Harry Gottlieb:

I mean, the short answer is we don’t know, here’s what we’re trying to do. We’re trying to fix how we make decisions. We’re trying to introduce a process that is a better process for making national decisions than what we are currently doing in Congress today. And it’s longterm, I mean… You’re looking at me like, “Okay.”

Whitney Kimball Coe:

So you can see my face but I mean, I agree. I know that real change and the real meaningful work is always long-term.

Harry Gottlieb:

This is a generation’s own pride. There’s already a generation of people who’ve been working on it. It just hasn’t hit the zeitgeists yet. We solve problems through an adversarial process right now. And that’s been going on since the first Congress. That does not need to be the way we do it.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Well, thank you for spending that time, rigorously talking through that with me. And I’m looking forward to watching the growth of Unify and participate in the long-term work. Because I think this is what we’re all working to do in this field. Thank you so much. And thank you for saying yes to joining me for this conversation and for being a great partner and look forward to seeing you at Rural Assembly Everywhere.

Harry Gottlieb:

All right. I’m excited. I’m excited for Rural Assembly.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Yeah. All right. Have a good day.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Next step on this episode is Kiran Singh Sirah who will deliver a keynote at Rural Assembly Everywhere, kicking us off on day two. Kiran is the President of the International Storytelling Center. He’s based in Tennessee’s oldest town Jonesborough, which is also the site of the well-known International Storytelling Festival. In our interview, I spoke with Kiran about the power of storytelling, the practice of porch sitting and St. Dolly Parton

Kiran Singh Sirah:

My work, I guess my passion, my heart is storytelling as a radical gift. I can change lives, change the world, that’s something that we can all do ourselves for ourselves and for our communities that we live in.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Why storytelling? Why do you say that is the thing at the heart of our lives and the thing that can move us?

Kiran Singh Sirah:

I think it is because it’s the thing that’s always made sense. When you think about throughout human history, we… I mean, you can go right back to our ancestors that etched pictographs onto cave walls to suggest that I am here or to communicate to generations after them or to make sense of the world to a NASA 1972 Pioneer Space Probe that NASA sent out into the universe with the same inscription drawn onto a plaque, a man and a woman. Inscribed with the idea that perhaps they’re making sense in case we come into contact with extraterrestrial beings that we can say they would understand where this spaceboat came from its origin. And I think when you think about all the great crucibles in human history, stories have been told about them. But stories are also the things that have shifted us to create new identities, new nations, it’s been used to foster propaganda.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

It’s a force, like the Jedi force, it can be used both for good and bad. Inherently it’s good, I believe, because it’s the idea it’s something that’s one of the most sacred, core aspects of our humanity. We all want our story to be received, to be heard, to be understood, to be appreciated, and to go into this movement. There’s something great in all of us, the story of us, who are we? Right, what are we looking towards? And it’s really important, but it goes right back down to Appalachia, right? The front porch, we sit on that front porch and you hear your stories of your family. Now the front porch is a liminal space is it’s a space that’s neither near the inside, nor outside. It’s post. It’s a space between, it’s a space that throughout southern history, it’s been known as the place that we have negotiated social norms.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

It’s a space that when it was unacceptable for black and white people to interact or families to interact over decades, it became the space that society negotiated there before you come inside the room. The globe is one big front porch, right now. We’re in this liminal space, we’re sitting on our grandfather’s knee or our grandmother’s knee. We’re hearing the stories of our traditions, where we come from, who we are, what’s our heritage, why do we exist? What’s our connection. What binds us? What are the lessons? And once we do that, we are reflecting about what are the things that we want to shape as we go forward as we move out into this outside world, beyond the front porch?

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Are we really doing that well right now, are we sitting on our front porches and having an exchange in ways that make us feel more connected, help us understand the world, help us feel more connected to us, as you mentioned, part of me feels and maybe it’s the cynic, are we doing that well at the moment? And how could we be doing it better, creating that narrative of us?

Kiran Singh Sirah:

I mean, I think people are doing this no matter where they are. I think artists are, that’s the way artists think and how artists are continually trying to make sense of the world and trying to think through these processes, anthropologists are social scientists are. I think what storytelling essentially helps you to do, Kathryn Tucker Windham talked about this, Kathryn Tucker Windham was a matriarch for this American story that a movement from Selma, Alabama. She died in 2010. And she always said, that what storytelling does is teach you the lesson. It’s essentially, it’s a tool, it’s a guide to help us to listen. And listening is this thing that helps us create these spaces where we are willing to be challenged and hear new ways of thinking about the world around us. When you listen in a way that’s truly listening, not listening for what you want to hear, but listening for where the teller is creating meaning, but offering their meaning.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

Then what we also do is that we are able to find how we can see ourselves in that person’s experience. The storyteller knows me, concept. I think about this, three people walk into a bar, a politician, electrician, sports coach, and they sit at the corner of that bar and for a while they watch football, drink a beer, but after a while they start sharing and that bar becomes the equalizer. It’s a place in which they can come and share, and they start sharing their story of themselves. They’re no longer the electrician, the politician, the sports coach, they’re three human beings that are having this opportunity to share.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

Now, if we can do that at the corner of that bar, then imagine we can do that in society. But between two nations, two groups, two communities, because it’s the space and the experience of sharing our heart, our values, our beliefs in a way that could help us bind and find the values in each other and build that empathy and empathy listening, I guess, in a sense builds that, leads to empathy, the understanding, and the understanding leads to connection and connection can lead to many other things, social movements, social change. But that connection is valid.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

We’ll be right back after this from The Daily Yonder.

Anya Slepyan:

Hi, I’m Anya with The Daily Yonder. The Daily Yonder provides news, commentary and analysis about and for rural America. We welcome photos, tips, observations, and links to stories about rural people and communities around the country. Send us your stories and follow our coverage at dailyonder.com.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Could you tell me a little bit about what it’s like to be a Sikh in East Tennessee?

Kiran Singh Sirah:

Well it doesn’t matter, there’s no Sikhs because we see everybody as Sikh.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Okay.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

Sikh just needs to be a disciple of life. And we have this philosophy in Sikhism where we imagine the Lotus flower, right? You imagine a Lotus flower, it’s this beautiful flower, right? And it lives, can emerge, it can flow up in this muddy pool of water. And it could be that single flower that sits by itself and shines new in the mud. And the Sikhs must always strive to be that light. We don’t have to be in community with other Sikhs, because we see the human race as one. And a Sikh must always be in prayer meditation, but the idea is our meditation have to be involved in justice fight for justice equality.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

A Sikh must also go out into the world by themselves and go on a journey and must embrace five religions that are not their own five traditions that are not their own. You don’t just listen to them. You have to fully embrace it. The poetry, the music, the language, and do it with the whole intention to understand the poetry, the beauty, the beliefs of a Christian, a Muslim, a Jew, a Catholic, a Protestant, a Jedi Knight, if you will.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

I love Jedis. Going back to star Wars. I know, but it’s this idea that when you have completed your journey of five then you understand what it means to be a Sikh. And you’re on a journey to discover, as Sikhism says, the first word in our Holy scriptures, one, the one Ik Onkar, the oneness of eternal of all life, all sentient being of the universe. And that humanity is one. And the idea is you’re working to dissolve the illusion that we’re separate. And you’re working to find the thread of connection that exists in all our humanity. And all our sentient beings and our connection to mother earth as well, and the universe around us. So in East Tennessee I go to churches, I go to mosque, I go to synagogue, it doesn’t matter. I go to social justice convenings. And to me, that’s what it means to be a Sikh.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

I also want to know what it’s on your front porch here in East Tennessee. Tell me, describe your front porch?

Kiran Singh Sirah:

Whitney, you ask the best questions! I have two rocking chairs. I have a little rocking chair for Dolly Parton. I have a miniature rocking chair that I’ve got a picture of Dolly Parton in it. And so me and Dolly rock on the porch. I’ll make [crosstalk 00:31:49]. I have a bunch of fairy lights that I keep up there year round. I have a whole bunch of Tibetan Kraft lights, and I have two flags, I have three flags actually, I have the Scottish flag, the union flag, the US flag and the United Nations flag in a little… Don’t have really big stands, but I have them in this little flag flower pot.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Cool. What about Dolly? You have an affinity for Dolly Parton. Can you tell me a little more about that?

Kiran Singh Sirah:

Well, Dolly is wonderful. She’s our state’s greatest storyteller, but one of the reasons that I think… We’re honored to be able to get to work with her team. And we worked a lot with them. The Dollywood’s DreamMore Resort based in Pigeon Forge in Sevier County.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Oh, so International Storytelling Center works with the Dolly team?

Kiran Singh Sirah:

Yeah.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Oh, how wonderful.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

We’ve worked with the Dolly team in many ways we’ve actually created a nonprofit private partnership about establishing how to connect storytelling and song and tradition in a way that connects the value and the beauties and the rich traditions of East Tennessee. So we actually host a little festival in January, February in Sevierville that brings songs as story and songwriters and builds community. And the first event was actually after the Gatlinburg wildfires. So in a way we filled up the hotel in a way that could bring people into a region when people really needed to spend the dollars. But on top of that, we also had done some training for the Imagination Library Team.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

Miss Dolly sent me some flowers to my room. So I made a little shrine for Miss Dolly, but another aspect of why we really value who she is as a shero, and in many ways she is a perfect example of The Hero’s Journey, Joseph Campbell’s concept of The Hero’s Journey, in that she came from poverty, she followed her dream and ambitions and ideas. She learned to harness her story. She went on a physical journey, which at that time was a long time, was a large distance to go from Appalachia to Nashville, where she came from, and she made it big. She becomes successful, right? And she became this international star, but then she always came back home and she shared her wisdom, knowledge, ideas, both physically and figuratively with the world and Appalachia. And in many ways what she did, she overcame those obstacles and she’s like the Greta Thunberg or the Emma Gonzalez or the Malala Yousafzai in a way that they’ve overcome the obstacles and used that experience to transform and share.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

And that’s why we called this program inspired after her, The Shero’s Journey where we work with young girls between the ages of 10 and 14, particularly because we know that young girls, they have less of an advantage than their male peers because of the social pressure on them. And so the idea that when they learn their story and then harness their story and then to re-author it, learn public skills and self-esteem in that way. And build peer solidarity, that it’s a way to empower this idea of the shero. And part of that was inspired by the Me Too movement, but not directly, we already created the program anyway. So that’s been one of our programs that have come out of this relationship with Dolly Parton and what she inspired. So I love Dolly, but there’s also a deeper connection because it relates to storytelling in a very integral way.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Yeah. I love how you said, she‘s the greatest storyteller of our time.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

Well, for our state.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

For our state. Okay, fine. What other storytellers inspire you these days? What are you reading or listening to?

Kiran Singh Sirah:

So I’m really a documentary film… I do read a little bit. I go for a walk in the evening and I’ve been reading a book and they’re putting it up on audible. It’s pretty cool actually, I’m reading this book called, Be My Guest, and it’s by Priya Basil and she actually reflects on food, community and the meaning of generosity. And she’s like me, she’s Sikh growing up in East Africa, but grew up British as a British citizen like me, but now lives with her husband in Berlin, I think, and she’s very pro European with the concept of the European identity. And she writes about food, she writes about Langar and traditional food, the way that we… Anyway, I’ve been reading that and it’s been nice to go for a walk and read some of that. I read a lot of articles and stuff, and I’ve been reading about Loretta Ross. Was it Loretta Ross? I think that’s when she talked about the whole calling out, calling in as opposed to calling out.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Yeah. I heard of her recently or somebody introduced me to her recently, this idea of calling in.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

Yeah. And I also like to binge watch The Crown. I’m on season four right now. And [inaudible 00:37:44]

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Yes. I’ve done both of those too.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

You know how it is. I mean read a bunch of books, but I don’t like to read thinking I’m wasting my time. I don’t want to waste my time. I just like to read stuff that’s about the world for the world, can help me get a better understanding of the world, people in society and in a way that can move us forward. I don’t mind [inaudible 00:38:13] but occasionally when I’m really just overloaded, sometimes I am, I just start to switch off and be a bit more mindless.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

I understand that too. So Kiran, thank you so much for spending time with me today. It was so good to talk to you and I look forward to seeing you at Rural Assembly Everywhere.

Kiran Singh Sirah:

Thank you. I look forward to it as well.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Thanks for listening. We hope you’ll join us for the upcoming virtual festival, Rural Assembly Everywhere on April 20th and 21st. Rural Assembly Everywhere is a virtual festival for the curious and critical the listeners and the connectors it’s geared toward rural allies, neighbors, and admirers. Please register for free today at ruralassembly.org/everywhere. We’d like to thank our media partner, The Daily Yonder. Everywhere Radio is a production of the Rural Assembly. Our senior producer is Joel Cohen, our associate producer is Anya Slepyan. And we’re grateful for the love and support of the whole team at the center for rural strategies. Love you, mean it. You can be anywhere we’ll be everywhere. Thanks for listening.