Tony Pipa is part policy wonk, part story teller. He focuses on connecting with policy makers, local leaders, and community members to reimagine federal rural policy to fit the needs of rural America. He uses his wide range of expertise to uplift stories of progress and success in rural communities.

We talk with the native rural Pennsylvanian about the diversity of rural America, his new podcast, and bringing the rural story to Washington D.C.

Show notes

* A Policy Renaissance Is Needed for Rural America to Thrive by Tony Pipa. A column in the New York Times published Dec. 27th

* Commentary: Why U.S. Rural Policy Should Matter to Everyone by Tony Pipa, published in the Daily Yonder April 13th

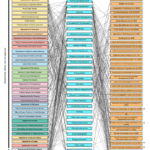

Whitney and Tony Pipa discuss this graphic. Pipa created it to demonstrate the complexity of federal development assistance for rural and tribal communities.

Whitney and Tony Pipa discuss this graphic. Pipa created it to demonstrate the complexity of federal development assistance for rural and tribal communities.

“It’s not very coherent. It’s pretty fragmented, and it makes it a real challenge for a rural community to figure out what really applies to them and their particular situation and what can they make best use of? And that’s even before getting into the actual application processes and how do those application processes disadvantage rural in particular ways,” Pipa said.

Tony Pipa is a senior fellow in the Center for Sustainable Development at the Brookings Institution. Tony launched and leads the Reimagining Federal Rural Policy initative, which seeks to modernize and transform U.S. federal policy to enable community and economic development in underserved rural places across the U.S. He hosts the Reimagine Rural podcast, which profiles rural towns across America that are making progress on their efforts to thrive amid social and economic change.

Tony serves as the vice-chair of the board of directors of StriveTogether; as a senior associate research fellow in the Global Cities program at the Italian Institute for International Political Studies; and as a member of several task forces and advisory committees. He grew up in rural Elysburg, Pennsylvania, in the heart of anthracite coal country and attended Stanford University, graduated from Duke University, and earned a Master of Public Administration at the Harvard Kennedy School.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Tony Pipa grew up in rural Elysburg, Pennsylvania in the heart of Anthracite coal country. He made his way to Stanford University and Duke after that, and then onto Harvard Kennedy School. Tony is now a senior fellow at the Center for Sustainable Development at the Brookings Institution. He launched and leads the Reimagining Rural Policy initiative, which seeks to modernize and transform US Federal policy to enable community and economic development in underserved rural places across the US. He’s also the host of the Reimagine Rural Podcast, which profiles rural towns across America that are making progress on their efforts to thrive amidst social and economic change.

Tony Pipa has contributed mightily to the field of rural policy through his research and advocacy, through his writing and his consistent call to not leave rural behind. I’m excited to catch up with him today to talk about his latest efforts to help us reimagine federal rural policy and to hear more about his podcast and the stories he’s elevating there.So welcome to Everywhere Radio, Tony Pipa. How are you?

Tony Pipa:

I’m wonderful, and it’s really a pleasure to be here. I’m so looking forward to this conversation. Thanks for having me, Whitney.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Absolutely, me too. And I really, I want to throw a big broad question at you to start us off, because I know you also think in macro terms too. I wonder where you think rural America sits in the nation’s consciousness right now. How do you see culture and politics and policy all informing how we think about and respond to rural?

Tony Pipa:

Well, on one side, generally when we talk about rural, we’re talking about our political divisions and political polarization. So, that dominates a lot of what we hear in the media. And when people talk about rural, that’s usually the frame of reference in which they’re talking about it from, and that’s honest and it’s true, and it really is a place in which our country right now, in terms of how we’re politically polarized, and there are difficulties in actually talking about our political differences, that often tends to collectivize itself into rural and less rural places or urban places.

At the same time, I think underneath all of that and going under recognized is the real opportunity that we’re on the cusp of for rural communities as the economy shifts and we try to reimagine what our energy systems will look like, what our food systems will look like, and frankly, how to ensure a fairer economy for all. And I think that’s a conversation that’s emerging, and it’s also emerging… There’s an emerging consciousness that rural needs to be included in that conversation. I think we saw after the murder of George Floyd and what happened in the pandemic, a real consciousness about what it meant for Black and Brown people in America.

But I also think as we shift to the new kinds of economies that we’re looking forward to, there’s an emerging consciousness that that’s going to have to include rural for the country as a whole to be sustainable and to be more fair, and frankly, to be whole in some way.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

I really appreciate that kind of giving us the broad landscape of where this conversation sits. And I also wonder if you have thoughts about how are rural people themselves influencing where it sits and what we’re talking about and why it’s important that they not be maligned or left behind.

Tony Pipa:

Right. And that’s the challenge. The voice of rural is not often heard in these big conversations. Everything from what does America competitiveness look like globally to even this switch to a clean energy economy. It’s just not often there. And the interesting thing is, rural sits at the heart of this, so let’s even just stay on the green economy. If we’re going to shift to a cleaner economy, rural’s going to be at the heart of that. If we’re going to increase solar, if we’re going to increase wind, if we’re going to need more minerals for batteries, if we’re going to have new kinds of manufacturing, everything from semiconductor chips to new batteries to new kinds of technology.

And rural places are actually already dealing with this. There’s lots of conversations going on in lots of communities across the United States about whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing to give up land to put a wind turbine on, and what’s that going to mean for the local agricultural systems? What’s it going to mean for new jobs? What’s it going to mean for communities, local governments and their revenue over time? And how do you do this well and how do you maximize the benefits and include as many people as possible in it?

But the struggles that those rural communities are having, those voices aren’t necessarily what’s informing the policy conversations at the macro level in Washington, D.C. And oh, that’s a little bit about the impetus for the podcast, frankly, is to hear directly from people in their communities that are making some headway on reinventing their communities and strengthening the economic and social resilience in their towns.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Yeah. I want to talk more about the Reimagining Rural podcast, but I’m also interested that… I mean, I’ve been following your work for a long time and reading your pieces, and they’ve had a really profound impact on how we think about rural, American rural policy in a large part because you do so much research and data aggregation, and there’s a lot of wonkiness to some of the reports that you’ve put out, and that is all really wonderful and helpful.

But I’ve seen this shift in the last couple of years, especially where you’ve had… It seems that you’ve grown more interested in perhaps narrative and stories and capturing people’s experiences and aligning them with that data and research that you’ve focused so much on over the years. So I wonder if you want to say a little bit about that, like your approach to proclaiming the rural gospel it now spans many things.

Tony Pipa :

Yeah. And I think you need both. So, I started with a basic question. How well are the federal resources that are being made available for community and economic development reaching rural places that could really benefit from it? And how well are they meeting those places needs? How well do they match up with what rural communities are really facing?

So, I kind of play a forensic accountant to start. I just started with where all the money starts in Washington, D.C. and then how does it travel and where does it travel to and what rural communities is it getting to? And I mean, we tried to visualize it. There’s over 400 programs spread throughout many different nooks and crannies in the Federal Government, and that makes it really hard for a rural community to even figure out, what’s in it for me? Like, what [inaudible 00:10:38].

Whitney Kimball Coe:

you produce this really incredible infographic at one point, and we should post it on our blog after this episode goes up. But it’s like this morass of all the different programs and the bills and policies that even mention rural and how they’re connected. And it just looks a mess, actually.

Tony Pipa:

Yeah. Yeah. It’s not very coherent. It’s pretty fragmented, and it makes it a real challenge for a rural community to figure out what really applies to them and their particular situation and what can they make best use of? And that’s even before getting into the actual application processes and how do those application processes disadvantage rural in particular ways.

And to your point, we came up with a lot of data around that. And one of the things that we found is that there’s kind of a presumption on the basis of the Federal Government that they’ve got a partner on the ground, and let’s just call it a local rural government, that can put up with all the requirements and all of that morass and they can figure it out. And then when they put all these requirements for an application process and the match requirements that come with it, and the reporting requirements come with it, that rural communities can sort of deal with all that.

And it seems like such a mismatch from what I was hearing from rural communities and talking to local mayors and local nonprofits and people who are working in their communities say, “Look, I’m one person. I’m a part-time mayor. I also do three other things in my community. And yeah, we’ve got this association, community association, or local nonprofit, but the person who does that work is also doing three other things.”

And I’ll just be honest and say, I just came down to it and said, part of what also gets in the way is this narrative of decline and this narrative of negativity that rural communities just aren’t going to make it. And there is, I think, even from an economist perspective, this idea that the way the economy works now, the way the global and national economy works now, is that it really privileges density. It privileges a lot of people in one place to really maximize efficiency. I’ll use those economist words. You’re going to want to be in a dense place where people can be connected and network together and be creative together. And it’s an innovation economy, it’s an information economy, those signs of things.

But I knew that there are rural places that are doing well, are seeing ways to thrive. And I felt like this narrative of decline is so overshadowed, everything else, that what we tend to start to doing is to say, “Okay, what’s broke that we can fix?” Rather than say, “Okay, what’s working and how do we make sure our policy is creating the environment and supporting, creating the conditions for what works, and then really supporting what works? How do we scale up what works rather than try to fix what’s broken everywhere?” And again, what is working is very diverse because rural America’s very diverse. There’s no one-size-fits-all for rural.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

And spend a moment there for a moment.

Tony Pipa:

Yeah.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

I mean, tell us about the diversity of rural? Because that comes up frequently in conversations around decline too, thinking that it’s such a monolith.

Tony Pipa :

Yeah, I mean, most people when they hear rural, they might think of a predominantly white, blue collar community. It might be in the Midwest. Many times it’s agriculture that pops into mind. But our rural America is very diverse geographically, economically, racially, it’s 24% people of color. Agriculture is actually at this point, 7% or less of the employment in rural economies. There’s a large sector of rural economies that are service oriented. There’s growing outdoor recreation and manufacturing continues to play a really important role throughout rural America as well.

And then geographically, think of the vast distances in the West when you’re in places like Montana or Wyoming, many of that public lands as well. And so oil and gas and energy leased off of public lands and large swaths of natural habitat versus where I grew up in north central Pennsylvania in the heart Athrocyte coal country. I grew up in a town of 1800 and went to elementary school in a town seven miles away that is now about 7,000 people. But we’re three hours due west of New York City. And all of that has real import for policy makers. So, from a policy perspective, you can’t be thinking of a one-size-fits-all solution for things because they’re very different communities. And that diversity really, I think speaks to how we need to start to think about how we invest in local people and the local assets that they have and the solutions that they see for themselves and the connection that they have to their own local, regional markets and economies versus thinking that we can create the solutions from Washington, D.C. for everybody.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

thinking about the notion of reimagining rural who needs to reimagine rural? We’ve identified in this conversation already policy makers, folks who write stories and tell or share or amplify them. And rural people themselves, I’m wondering if there was anything you heard in your conversations that made you even reimagine some of your own notions and the research that you’ve been immersed in for years and years? Was there anything that surprised you and really stretched your imagination a bit?

Tony Pipa:

Yeah, a couple of things. So I use the word reimagine as a way for us to also reimagine the narrative around rural, to have it be a narrative of opportunity and growth and sustainability rather than a narrative of decline and challenges. And each of the people that I talked to and the places where I was visiting talked about how they often reimagining their own community. And one of the themes that actually really surprised me, and as you said, a lot of the work I’ve done has been very wonky. I kind of have a sense, and I had my own experience even working philanthropically to support community economic development of the technical aspects, putting the plans-

Whitney Kimball Coe:

And I think wonky is important and good. I just want to say that.

Tony Pipa:

Bringing people together and executing on some ideas and how do we get capital in? How do we use the public financing to bring in the private financing, all those. How do we link up local entrepreneurs to larger markets? All those kinds of wonky things. But from the very first interview, a theme emerged that just became consistent throughout that I didn’t really expect. And that was the idea of beauty, that each of the leaders that I was talking to talked about how important it was just to make their places and their homes and their neighborhoods and their communities beautiful. And how important that beauty was to their overall prospects for reimagining their communities and renewing their communities.

I started in a town where I went to elementary school. It’s not the town I grew up in, but it is a town where I went to elementary school, Shamokin, Pennsylvania. And in speaking to the former mayor, he was talking about how when he became a… He had been a policeman for 20 years, and then he retired and he still wanted to be active in the community, so he started to run for public office, and he ended up as mayor. And he said, “I became mayor and I start to make the rounds, and I’m looking for…” And Shamokin has been a place which since my lifetime, has really significantly had its share of challenges and seen its economic prospects really diminish. It’s a town where poverty is above 30% now. The town has lost about 40% of its populations since I went to elementary school.

And so former Mayor Brown was talking about making the rounds, looking at Blake, looking at the code violations and things that he would need to take to city council meetings and talk about, while his wife in the car was looking at housing saying, “Wow, look at that house. Look at what they’ve done with their porch there. Look what they’ve done here.” And she was seeing the beauty that people were creating with their places. And it started to open up his eyes. And as they started to make their rounds, began to buy potted flowers and put notes of thanks in those potted flowers and just leave them on the porch or the doorstep of the houses that they were noticing. And said that the reaction and the response they got was phenomenal. About, “How can I be helpful? How can we work together? How can we come together as a community to kind of reimagine and go forward as a community?”

And my second interview was an investor, Kathy Vitovic, in the same town who had grown up in Shamokin, gone away to school, spent a couple years in Kansas City, and then just wanted to move back because she felt like that she wanted to be, as she said, like they say on Cheers. She wanted to be in a place where everybody knew their name. And she had gotten that point in her career where she then had some assets to be able to invest back in her hometown. And she bought a building, a building that had fallen into disrepair on the street. And she said, “I bought that building and my whole goal was just to make it beautiful, just fix it up.” And it turned into a restaurant that she ended up calling the Heritage Restaurant. She put a bunch of artifacts from the history of the town, which is a former coal mining town, and almost created a little feel of the museum in the restaurant. And it became quite a gathering place for the community.

I mean, the other thing that they encountered is they bring new ideas to their communities. They often encountered resistance or apathy. Change is hard, even change at a neighborhood level. And it was a way to, I think, unlock what’s important for communities to flourish and to build trust and to build a sense of unity as well, and hope. I think that’s the other thing that we tend to underestimate the importance of, is we look at policy through a quantitative, economic lens and try to create our inventions based on those things. But the importance of the community’s identity, its psychology and how it perceives what’s possible, i.e. the sense of hope or the degree of hope a community might have has been actually really important in the places that I visited.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Oh, I’m so glad you unpacked a little bit of that. I think that resonates with my own experience of living in a small town and the people that I know and visit in other places. In fact, some of our rural strategies staff and board were just in Fleming-Neon, Kentucky, which was a site of devastation just last year in July after that horrific flood passed through. And in downtown, there’s some really great folks who have just bought a building to shape it up into a place that can be a gathering place, a place to feel some pride and enjoyment of one another to create some beauty in downtown Fleming-Neon. So, I mean, all of that just really resonates.

And then there are other conversations that I’ve been in of late, mostly in urban centric spaces where I’m asked the question, “Why should we care so much about rural survival and not letting it fall away or be left behind, more than just, ‘Oh, because rural is part of feeding, fueling our country?'” And I do also come back to this notion of sort of heartbeat and connectivity and joy and our interdependency extends beyond the use of a place, but to the actual just being in existence of it.

Tony Pipa :

what I also found in the places that I visited, especially ones that are making some positive steps along this… What can sometimes be a very long continuum to renew themselves, especially if they’ve experienced challenges for a long time… Was I really believe that we’re going to build our muscle of working together at the local level. And these communities really highlighted that, for me.

I mean, it was also striking the extent to which… Because we talk about local leadership all the time, it’s about building that momentum. But it was striking to me the extent to which that momentum began to build because of collaboration or because of people coming together and working together. And it’s not just all work, it’s sharing a sense of identity, it’s sharing stories, it’s sharing histories, it’s acknowledging when those histories have been negative rather than positive. And it’s honoring what came before. One of the things that the leaders that I talked to were very instinctively good at, this was not done in any planned way, but instinctively good at honoring the past and an identity that may have been, but that was not going to be their community’s identity for the future, just because things had changed, because the economy had changed or the surrounding area had changed or whatever.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

And I understand our conversation might be winding down, but there was one other question I wanted to ask you about you yourself, Tony Pipa, and you were living in D.C. You come from a rural background. You are occupying a space that many of us who feel affiliated with rural livelihoods and outcomes are living in, which is kind of this bridging of geography and experience. And I wonder, how’s it going for you in that space of, I let you live in, around D.C. but you’re also so tied to rural communities and rural livelihoods?

Tony Pipa:

I think what I really feel privileged to be is that I feel like one of the values that I learned growing up in a rural town is, lack of a better word, stewardship. And I feel like I’m being the steward and kind of the pass through for stories from different places across the country.

And so if I can use the networks and the connections I’m able to build to policy makers, to people in Washington, D.C. who are making decisions that will affect us as a country, if I can be a steward of stories that can really inform that, I feel like I’m putting myself to some good use. And also being able to translate those stories into the language that a policy wonkery, right?

Whitney:

Sure.

Tony Pipa

And how we make decisions based on that. And being connected to people from where I grew up, and also lots of other people in rural places across the country, keeps me honest in doing that, and also gives me a lot of great places to visit.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

That’s lovely. No, that’s wonderful. Well, before I let you go, I want to ask you the question I get to ask all guests, and it’s one of my favorite parts, is to hear about recommendations from you about what you’re listening to or watching or other podcasts you might be into that you feel like would inspire others or maybe challenge us in all the right ways?

Tony Pipa:

Well, I’m an old English major, so I spent lots of my time reading rather than listening, oddly enough. So, I’m reading right now, Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead, which I think is fantastic, having read Charles Dickens growing up, and she kind of uses David Copperfield as a launching off point for what’s happening in Appalachia. And so highly recommended and also pretty amazing how a woman at her age can channel kind of a young boy growing up in Appalachia as well.

And then I would also say anything by Elizabeth Strout, I am just a fan, everything from Olive Kitteridge to her latest, Lucy by the Sea. But I actually just… I hadn’t read The Burgess Boys and I just finished it. And I just think the empathy and the understanding that she actually has of not just rural, but also people across different economic strata and urban as well, is really remarkable and a really remarkable lens onto how we can be empathetic with each other as well.

Whitney Kimball Coe:

Those are wonderful recommendations, both of them. And I say that too, having enjoyed both of those reads or all of those reads as well. Well, Tony, thank you for this conversation. I commend Reimagine Rural podcast to all of our listeners. You can find it on all platforms and whatever platform you prefer. But looking forward to the second season, and thank you for all the good work you do in the world.

Tony Pipa :

Thank you. And thank you for all the work that you do and what the Center does and the Rural Assembly and for this podcast as well. And I just love also having these conversations and love having these conversations with you. So, thanks very much for having me on.

Whitney:

Thank you.