My name is Anna Sullivan, resident of Athens, Tennessee. Born and raised here on Free Hill. Out of Free Hill, there are doctors, lawyers, ministers, nurses, baseball players. It goes on and on and on as to what we have done based on the fact that Free Hill laid a foundation for us. You must go to school. You must become educated. You don’t want to work like we do for 50 cents an hour and hand me downs.

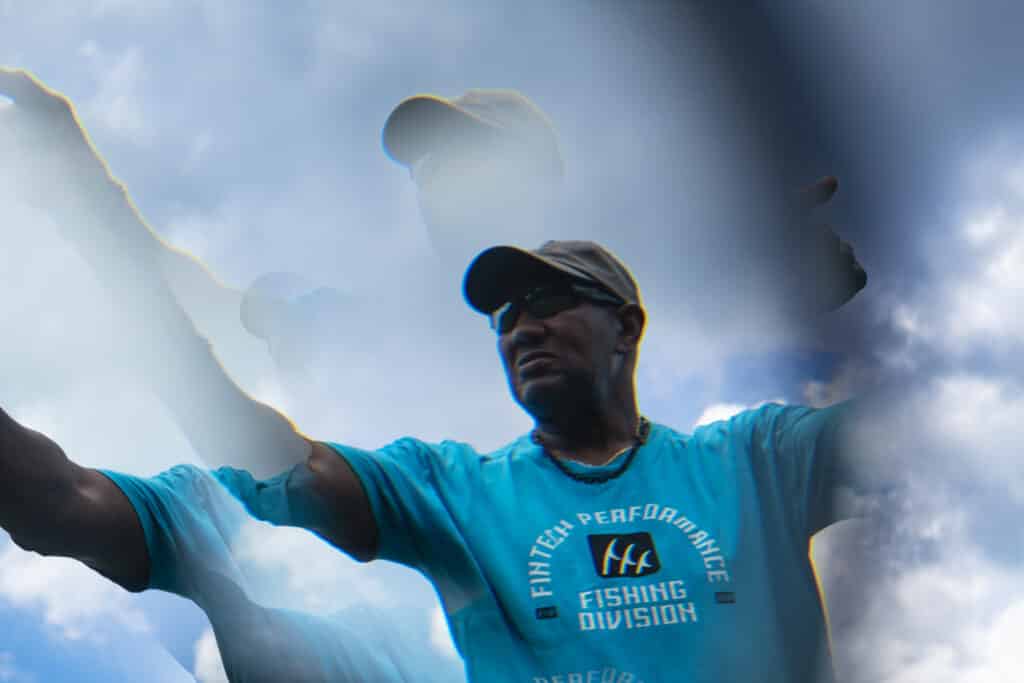

My name is Larry McMahan. I lived on Free Hill between the years of 1956 to 1968, is when I went into the Army. 67, I’m sorry. And I’m 73 years old and I lived on Free Hill. I experienced Free Hill. I grew up on Free Hill. Now we were in the projects. We was in nice projects, so we never did have to move out, but our friends and our neighbors and a lot of Free Hill were moved out of their houses and they never recovered from, they never got a penny from it.

My name is Vant. That’s V as in Victor, A-N-T. Last name is Hardaway, H-A-R-D-A-W-A-Y. I moved to Athens from Birmingham, Alabama in July of 1957, and I lived in the area we now call Free Hill until, I think it was probably 1965.

We moved to another area in Athens and I stayed there from 60… 65, 66. We moved in two houses during that one period of time, relocating, and I stayed there until 1971. 1971 I graduated from undergraduate school at Tennessee Wesleyan College. Then I moved away, lived in Oak Ridge for… Was a teacher and a coach from 71 until 78 and 78 I moved to Nashville, Tennessee and I returned to Athens in 1986. And so I lived here the rest of those times. The picture I may paint may be a little different from some others. I was relocated after being seven. Now, from the time I was seven until I was about 16, I lived in the Free Hill area. So with that it went and the way mine ended up, the way I ended up may have been different from others because I was sort of reset with it. And as a result of some, not just the Free Hill part, but just the whole of the segregated part and the merging and the desegregation of it all, would’ve made some things different for me.

I was pleased when they did get a marker saying, “We recognize.” That’s the reason I said whatever questions or whatever thoughts and whatever I may say may sound different from some others because mine may be a totally different experience. I really didn’t even know how we got the Free Hill name because I moved into it when my parents moved here. When we moved there at seven, my dad was a minister and so we moved there because our church was one of the churches in that area.

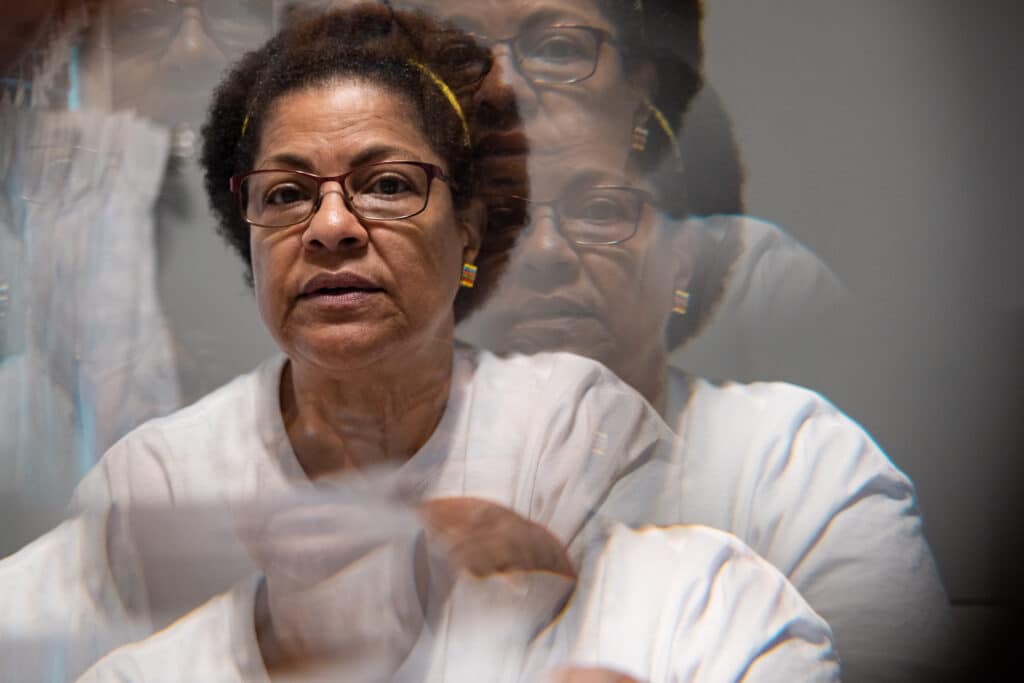

My name is Cynthia Webb McCowan. I’ve lived here 27 years, but I am originally from Mississippi. My connection to Free Hill came with doing a Black History Month program for the Arts Center, the Athens Area Council for the Arts. And while we were brainstorming or what I call whirl-winding ideas on how to present something different, we came up with the idea of doing what I call stage stories — stories you tell on stage — but knew that not a lot of black people here would be comfortable being on stage. They’re not theater people. So we came up with the idea of doing just conversations. Linda Long was part of the brainstorming process, and she asked that we consider doing Free Hill, which I knew nothing about. And so when we delved into that, I learned a lot about Free Hill and the life that they had on Free Hill, the community, the culture, and the demise. And so my connection to it now is to do the research to establish and find out definitively what a Free Blacks started there and to document with a historical marker, the demise of Free Hill. So I am their spokesperson, their researcher, their facilitator, but I did not live on Free Hill. That’s my connection to it.

Being on Free Hill back then, I was born and raised there and my grandparents, Maddy and Jess who raised me and my siblings and other grandchildren. And out of the flock, I was one of the youngest one.

I have enjoyed my life. As a child growing up, I felt free, safe, uninhibited, no worries, no concerns. Had an opportunity to live life as a child. We did not know of the issues that our parents endured because things were kept from children. We were allowed to be children to play, to enjoy, to eat. We had no clues where things were coming from. We didn’t realize the hardships that our parents endured, our grandparents especially. And they would borrow from each other and it was no payback. And they would share. And if one neighbor had too much of the something green vegetables, they would share or my grandmother. Who had a big family, boys and girls, and many, many grandchildren and great-grandchildren. For Free Hill to be taken from us. That was like taking a piece of our lives because we grew up in a safe haven. Free Hill was a safe haven for the grandchildren and the great-grandchildren because it was a community and everybody was family. There was once a year, entire Free Hill, they would take all of the children to what they call field of the wood. And there were no amusement rides. It was just different scriptures written on plaques, steps to walk here again, they kept us all safe. We always felt safe. We always felt protected. And we were never exposed to what I would call the outside world. Being the white world.

We were good. We did like typical kids do. We played, we fought, we played, we fought. Nothing major. All of it. Just typical things the kid did. And my mother, she worked as a domestic worker in people’s houses. I think she had about four different people she worked for. And we ate every day. We didn’t complain about anything. And we just lived life to the fullest that we knew how to live. And we went to a all black school called J.L. Cook School, which is here in Athens. And I went to the Cook from my first grade till my junior year, which was the last year I was integrated into McMinn County High School. And we had to walk to school every day, we didn’t have all these in-service days. I think we had about three major holidays, which were Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s. And growing up in Free Hill, we went out and played every day, went down the hill, our parents reminded us; “Watch out for each other” “Don’t get in any trouble.” Which we didn’t get any major troubles and stuff like that. And we just had a time where we just grew up in a segregated situation. But we didn’t really experience the segregation. I’m trying to say we didn’t experience these segregation as a whole, like most people did. We had to go to the colored, had signs out for colored, and they had water fountains said colored. Cause I remember first kind of realized that it was a difference. In my lifetime growing up in Free Hill, I never experienced racism as a personal thing. It was just ingrained. And they kind of told you what to do, what not to do. And you just kind of walked along. You didn’t question anything. You just went along with the process. But the integration part, I never experienced anything the first year at McMinn and I was in the first class to integrate at McMinn County High School, and it went all right.

I lived in Free Hill, the area that we called Free Hill. It was totally unique situation because we were there. And while it was part of the wider community, it was not a separate community, it was just separate because it was segregated primarily. Now, there were some Caucasians that lived in that general area. They were in the minority, but the bulk of us were there and there were some whites that lived there. But here again, it was just another part of Athens. We would walk from Free Hill into whatever area of Athens we needed to walk to, whether we were going to go downtown or whether we would go from one side of town or something. But it was part of the wider Athens area. But it was just our community, which was pretty much our area. My years there, I moved there in 1957. So from 1957 until 1966, the things that come to my mind is the relationships, the camaraderie, the people we played with, the people we went to, it was our community. I can remember while one of the gentlemen that was with you all this morning, Larry, they lived in the housing development which was two or three blocks away; but we were all in there. So we used to go from there over to J.L. Cook School, and you may know where Cook Park is. But we would say, walk to school together or run to school together. And so what we remember is those were the things we did together, that was our camaraderie. Families were together. We got along with everyone because here again, when we were talking about 57 until 66, and that’s when we move- well, 65, 66. That’s when the area of Free Hill started to break down and people began to move out. While we went into downtown; but then we would return to our area and it was called Free Hill. But there was one, two, three, it was about four to six streets, many of them short streets. I remember the relationships. I remember the people, my friends.

It was a truly a safe haven for them, especially in the time of civil strife. When you live in a microcosm like that, your own little place where your people are, it’s a place you can go to after you’ve come from the outside world of racism and segregation. To be able to go into a community, a complete community that was almost self-sustaining and cohesive in how they loved each other and helped each other. And to lie down at night, in peace and safety, and take a break from being treated like a second-class citizen. That’s what it was to them. And that’s what my community and little tiny town I lived in Mississippi was, it was “this is ours”. There are no white people here to hurt us, to bug us. They live on the other side of town. And that’s what they had. And maybe that’s part of why I care so much, is because I realize what they lost. They lost that.

I would go to the grocery store with my grandmother and we would go back to the meat department. And the store was called Robinson’s. And she would ask Mr. Robinson, “Do you have any dog bones?” And he would say, “Yes.” And he would wrap all of these bones up. And I remember I was in the store with my grandmother one day and I said, “Why are you buying dog bones?” And she tapped me lightly on the head and she shook her head. That meant be quiet. After we got back to the house, we went out, got in the taxi, got back to her house. She said, “Now, let me tell you about these bones.” She said, “These are neck bones. They are bones that are loaded with meat.” And she showed me the bone. She opened up the package. She said, “I’m going to cook these and the boys are going to eat them.” She said, “In order for me to get these, they throw them away. I tell them I want them for the dog and they give them to me. They don’t discard them. They give them to me for the dog.” Which there was no dog. But that was how she was able to get these neck bones that were loaded with meat that they would just discard. She would also buy the soft bananas, the bananas that later on in life I learned that the whites would not buy. They would buy the firm bananas. Now, I learned all of this after I became a teenager. Growing up as a child, it was just a life to me and I understood it to be a good life, not realizing that on the other side of the road that there was this population of Caucasians or white people, as we called them, who lived, and we grew up growing hand-me-downs from the white family. We knew that our grandmother worked for a wealthy family in Athens. The white family, would give my grandmother their girls’ clothes. My grandmother would bring the clothes home and there was five older granddaughters between my grandmother’s daughters and she would divide the clothes that she had. And I don’t want to call the name. I could call the name. Maybe I shouldn’t. But they were a wealthy family. They owned the clothing store downtown Athens. And she would divide the clothes, which were real expensive clothes. We had an opportunity to wear nice outfits, but they were hand-me-downs. Here, again, we did not realize what was going on. We had no clue. Our lives were… I’ll use the word perfect. In the world that we lived in, everything was fine, everything was good. We were happy. We were full. We were allowed to run around all day because we didn’t have to worry about any anybody snatching us up, taking us off somewhere. We never heard of anyone being raped on Free Hill. We were safe to walk when it was dark. We felt okay.

I think most of our time we listened to the radio. When the Lone Ranger come on in the evening, everybody quit playing and run to the house and listen to the Lone Ranger on the radio. And then after that was over then we’d go back outside and start playing. And wasn’t a lot of people fighting and shooting and carrying on. Of course, we had lot of people. A lot of people in Free Hill was alcoholics. You could see them drunk and stuff like that, but the only time we saw white people in Free Hill was come time to vote. Then they would show up and the guys that were eligible to vote, they would give them a half a pint of liquor and tell them who to vote for and more or less buy the votes. And of course we saw that and experienced that. And we was always wondering, why would they show up always on election day? But they would. And then you had some, they’d pay some black people that had cars to pick up people, take them to the polls and tell them who to vote for. And they’d come back and get half a pint of liquor and then they would get drunk, all of that. And you’d see them passed out on the side the road, which you don’t see. You don’t see now but we saw a few in Free Hill, but every community had those. But we had a few that were doing that.

When a lot of the research was done on Free Hill was Burkett Witt. You may have heard that name. Some of the ones in the group may say, “Well, Uncle Burkett did this one.” He is right now 96 years old. He was probably a business leader. He ended up into city government because he was the first Black mayor in the state of Tennessee and he stayed in city council for 30 plus years. He was a part of some of those decision making, but it was not a lot of people in “Free Hill” that was a part of making the decision. And society was different in the 1960s, but it was not many Black folk at that time active in the workings within the city.

There had been a time in Athens, Tennessee when there were a lot more business owners. There were a lot of people. There were barbers. There were restaurant owners. There were other people that… Yeah, yeah. Just go ahead and get that. But those things, we missed some of that. And so as those people didn’t do it, if someone in their family didn’t pick that up and continue to pursue it. We have a few businesses that are still active. One is a funeral home business in Athens and it’s still very viable. Some of the churches still work to be viable in name, but it’s a challenge. We were not in the decision making parts of that.

The white people are taken care of. They have transitional wealth or generational wealth and they pass it on to their offspring, to their children and their grandchildren. When they strip you of your economic potential for growth, you have no generational wealth or no transitional wealth to pass on to the next generation. That barbershop that they probably could have, and the beauty shop and the hog processing thing that could have been a meat processing plant, those dreams didn’t get to be realized because they nipped that in the bud. They nixed all that. The barber could only cut white people’s hair. You’re a barber, but you could not cut Black people’s hair, your own people. You could go downtown, where we were, Robert E. Lee or whatever, and you could do white people’s hair. The tinsmith thing was downtown, but you couldn’t do it for the hog processing plant that Jess Gaddes owned. From what I understand, he couldn’t process meat for his own people. The white people brought him their hogs and he processed for them and the Black people got the scraps.

And then along came something that we didn’t even know. We were never told about it. There was a series of fires. Like I said, as children, our parents knew about the process happening to buy the property. But we went to bed one night and our parents awakened up and said, “We have to get out of the house. We have to go.” And there was a fire. All of Free Hill would congregate in one area together, and we would watch the fire. I never remember the fire department coming to put out the fire. I just remember that the empty house burned down.

As children, we were curious and we would ask, “How did the fire happen? Who did it? Why is the house burning?” We were so young. Our parents would never tell us, our grandparents would never say. Then the next night we would go to bed and we would be awakened. “Come on, we have to go. Another house is on fire.” So we were never told that the empty houses were being destroyed to keep other residents from moving in to Free Hill. They were forcing our grandparents and the other property owners to sell their property. We never knew who they were. Our grandparents, our parents never told us. It was just that our grandparents said we have to move. And that was it.

Free Hill, at the time, people that had houses, they called an imminent domain and they condemned houses. They was moving people out, not giving them what they said they were going to. It was supposed to be an urban renewal, and they were supposed to give people money for the houses, and they were going to move them out. They’d be the first ones to get the bid on the houses when they get their renewal change built up. But that didn’t happen. They were moved out, and every night the house was tore down and bulldozed in a big heap. That same night, it would catch on fire. We as kids would see that every night. We was little scared then, because we trying to figure out why they burn all these houses, but you never seen anybody to burn them. They would sneak up. Sometimes whoever it was, they would burn them houses at night, every night until they got all of them burn up. Then they’d just push them in a pile. Then they had to pay to carry them off. They would bulldoze them in a pile, and then they set them on fire night. Then the people got cheated out of their land. Now, we were in the projects. We was in nice projects, so we never did have to move out. But our friends and our neighbors and a lot of Free Hill were moved out of their houses and they never recovered from … they never got a penny from it, because if you didn’t own your house, then you was going to get cheated. You were going to be moved out and kicked out. More or less, you were kicked out of your own house. Speaker 2 (04:23): Because urban … called the hood, and that came in. There never was a meeting … because we were kids at the time. There never was a meeting that I know of that they explained this to people, but they said it was, because they told them that they could move back. They’d be given the first opportunity to move back into the new … first bid on the property when they got them leveled out and bulldozed out. But it didn’t go like that. It went to TWC. It went to Tennessee Wesleyan [inaudible 00:05:04] moved out. And to this day, nobody’s ever got money back from when they were moved out. They lost property, lost houses. They lost everything that they had. They were moved out and never had a chance to get back in, to go back in. Never got a chance to bid on the property because it was already sold before … I believe it was already sold before they even moved them out.

I’m sure you’ve heard about times when there were fires set. Now some may know more than I know, or may have their perception as to how it happened. It may seem like, “Well, that was somebody’s plan to close it down.” But I didn’t know that that well for them, because here again, I’m a teenager, a youngster, and really not able to know how my parents did their decisions. I remember when we moved, when it finally decided after some of the houses began to move, and people that were there began to move away and they were going to relocate that, the term that I remember hearing people talk about was urban renewal. Well, the church where my dad pastored, a OH church of God, it was right on Raven street. Well, we lived in the house, which was called the parsonage, right behind the church. When things began to happen and as decisions were being made, I can remember my dad and probably some of the adult members of the church, they got to a point where they made the decisions then of how we go. I can remember us moving to another house, but I think some of that movement went with, I guess, some decision of how we got there. I can remember when that church was moved. It moved to another place. Then the church that was bought, which was on the other side of town, it’s now on Ohio Avenue. That was the church that was, I guess, bought with whatever funds the church got from there. There was a house right across the street. We used that house as a “parsonage.” We lived there for … oh, goodness. Until I was in college. I went to college down in Tennessee, Wesleyan. Tennessee Wesleyan now was on the outskirts of “Free Hill.” Speaker 4 (10:29): Because there may be some that says, I know who did that. I can’t say I know who they were, because I didn’t. I think as it came down, I could not definitively say that that was the leadership, that as people moved out of the houses, set on fire and burned them down. Now, I don’t know how those people got money. I don’t know what kind of retribution they got. I don’t know if the people’s house burned. I know everybody that lived in the area, when the area step kept changing and kept moving, they ended up going somewhere to live. Now, I don’t know if they lived in public housing.

I know we didn’t, because when the church moved the church, they had some amount of obviously funds to get another building, and they got us some funds that got another “parsonage.” We lived in that until my mother and dad … eventually my mother decided, “Hey, I want to buy my own house.” But that wasn’t as a part of the urban renewal. That was my mom saying, “Hey, I got a job that I’m going to have me a house. So nobody will ever be able to move me away.”

But I can remember back then when the houses started to burning down, they only burnt down the houses that were empty. I remember the two houses that burnt, me, myself, and the siblings, when they did, they would do it at night. And quite naturally we would be looking out the window. “Oh, Grandma, Grandma, a house is on fire.” Back then the parents would just say, “It’s okay. It’s okay, go back in here.” And we would do just that. Then the next night came along. There was another empty house that caught on fire. Same thing, “Grandma, Grandma, Poppa, there’s a house on fire.” “It’s okay. Go back in here.”

Well at the time, as a kid, didn’t know what was going on. And yes, it would scare you when you see fire. Any kid. You see fire and you wondering what’s going on. But at that time we didn’t know what was going on ’cause back in the days, older people didn’t talk to the younger children. You was always in a child’s place. And that’s just the way it was. After I had got older, after I had gotten older, older and really, really knew what had happened, how talk gets around just Durban come in here and did this. That’s just listening as I got older, hearing other people talk. How the property came about for TW to get it. It’s an urban renewal thing, they say.

I’m still angry. I am so angry that they wanted Free Hill for the college. Here again, years and years and we never know why they wanted Free Hill. They wanted to expand the college. That was one of the facets. To expand what was then Tennessee Wesleyan College where I attended. I was one of the first maybe seven or eight blacks that attended Tennessee Wesleyan College then, which is a Methodist university. They wanted that, they wanted to acquire that property. So they came in and they took it. The most horrible way is to start burning houses that are empty to stop the influx of people coming in. And then to place fear in the hearts of children who seeing flames fly up in the air and don’t understand why. Why are these fires? Why every night do we have to go out? It ended finally because they burned down all of the empty homes. So there was a lot of fear in us and it was never dealt with by our parents because there was not a lot of discussion about it. But I’m still angry at 73 years old. I am angry that they stole Free Hill from us. That they took us from our safe haven. They took us from our world. They didn’t want us to be a part of their world. So they let us stay on Free Hill. And my grandparents owned their property, they owned their home. But when the white man got ready to take, then they took from us. They took from us, all we knew as children. We were okay. Why did they come in and destroy our world? We did not bother their world. So why would they come in and disrupt our lives and displace us because of something that they wanted? And then they didn’t even give our grandparents the monies that they were due. Why? Because the white man was able to do to the black man whatever he wanted without any repercussion. But they do not realize that they affected the lives of many children who are now adults, who are productive citizens of the city of Athens. And they still don’t recognize us. My uncle Burkett Witt was the mayor of this city and they still. And why Uncle Burkett? Uncle Burkett is still alive today, 95 I believe. But they took his mother’s property. And she owned acreage, but they took hers. They didn’t care. They didn’t care about us. They didn’t. No one sat at the table and said, okay, what impact will it have on the lives of those children? The adults are already grown. They’ve already lived their lives. What impact are we having on those children that we are displacing? They put us in the projects and that’s where we finished maturing into adulthood.

Free Hill was important to Athens because it was a part of Athens. They erased a part of Athens. You erased it, you moved it. So who could tell a part about Free Hill except you that lived there? If I went to another neighborhood in the city of Athens and took away their houses and their homes, that wouldn’t be kosher with them. So we have one, we had a neighborhood out of many, so why would you erase one neighborhood, the history of one neighborhood and leave the history of the other neighborhoods? And erase that part of history of Athens? That’s what we experienced in our history books. And it’s not in the history books. That is the way it was going all over the whole country. Even up to now. The black neighborhoods is the first one that they will erase because it’s easy to do it.

You don’t have, a lot of people didn’t own their homes. A lot of people were renting and a lot of people wasn’t making an income to buy a home. Cause you had to go through a lot of stuff back then as far as getting loan. Black people couldn’t get a loan like white people did. And I’m not prejudice, I’m just saying the facts. And even up date, they couldn’t get a loan. They didn’t have the jobs to make the income that they need to make to be able to buy a home. To pay the taxes, pay the insurance and everything has that goes with it.

So it is always been easier in this country to eliminate the black neighborhood first. If you want to move something out of the way, you going to go to the black neighborhood. The Indians went through the same thing. Look at your history and see how many black neighborhood has been eliminated in this country. Cause politicians get together and they’ll decide on, well we going to do this, we going to do that. And they’ll do it and move it. It was planned. It’s in the process. It’s a process. Always has been a process. The Indians will move out of their territory because of eminent domain. Because they wanted that property. They said they was holding up the progress of the country. I don’t believe that. You are a part of the country. You’re born and raised and served in the military and worked, paid taxes. You are part of that city, that county, that state, that country. So that’s what we lost in Free Hill, and other communities have lost the same thing in this country, because you erase the history of our people. If you own, everybody wants to own their own homes. I am a homeowner now. But everybody wants to own their own home and property and have stuff that they’ve worked for. Everybody wants that in America. Should anyway. But that was taken away and I didn’t like how my friends were displaced. They were kicked out, more or less.

What I understand it to be now, and what I understood then. See, here again, I was a 15, 16 year old teenager, so I really didn’t know. I just knew the statements that were being said, and some of it I did get from my parents, was that it was going to be redeveloped in that area because that area was somewhat depressed. The houses were not up to date. They were sort of down houses, and so some of the things we moved away from. There were some houses still in that area, probably still had some outside plumbing, while where we were, we had indoor plumbing, but some of it was outdoor plumbing. So it was a depressed area. Houses were not overly developed.

Urban renewal is, there was going to be a changing in that part of the community. So then, I didn’t know what was going to happen, but I knew some people were going to be moving and there was going to be some housing and some property changes, and then developing some more. And I think that’s what tended to happen. But in order for that to happen, there was going to need to be some restructuring. I don’t know necessarily if I could verbalize quote unquote retribution, because I don’t know what the retribution would be and to who it would be to. Because, here again, many of us have of moved into other areas and what sometimes and each person would have to see it their own way, or where for them, I don’t know how their life was at that time. The ones that are still there, I don’t think we would go back into those similar circumstances. So the life would not be the same.

The things we have to decide, how do I remember what was going on in my life and what do I feel like I lost? What do I need someone to get me back? As I said, I really wouldn’t, I’m not in a position where I could say anybody took anything financially or of value from us, because here again, my parents were the ones that worked through the situation. And so when we moved, the church moved. It moved to another place when we moved to another house.

I joined the military right after I graduated from high school, and my other siblings, they went on to do what they had to do. And you think about it. It goes through your mind. Well, why would they do us like that? Just to get whatever they were after. Didn’t know at the time that they were really after the property. We didn’t know that. All we know is a house burning here, one burning there, and you got to move. You got to move your family.

I went to Tennessee, Wesleyan, had a struggle going there. Here again, four or five blocks on a campus of a white private Methodist college. A struggle. A struggle because we still had to deal with the racist instructors. I only encountered one, and that was in the education department, which is where I was. I could not leave home because I had two children, had divorced my husband so I had to stay home with my parents. I didn’t live with them. Because that’s another thing. We were forced to move out and become independent.

Graduated from Tennessee, Wesleyan. Thought I had a job in the school district here, and didn’t get it because the city manager told me, “I thought I could get you the job, but I promised it to a friend of mine.” So, they gave it to a white girl. So, I had to leave, and I moved to Cleveland, Ohio, and became very successful. But I’m back home. This is home. You should always be able to go back home. I was able to come back home. Many of Free Hill residents that I grew up with are still here. Still here. I see Free Hill every day. I see the property every day. And every day that I see it, that I pass it, I think about how they took from children who were in a safe haven. We were not bothering anybody. We were okay.

I graduated from high school in June of ’67, and I went into the Army. So, that’s when I left Free Hill. When I came back it was different. It was changed. Had a YMCA. TDFC put a soccer field on it, and everything was covered up. Free Hill was covered up. Home was history to me because I experienced it. But other than that, it made me want to keep going on. I didn’t let it deter me, but I was disappointed that it was gone because I know that a lot of kids that were behind me could experience the same thing I experienced. And I was disappointed that what they said they was going to do didn’t happen. It’s a big lie. It wasn’t the truth. It was just to move people out. The existence of Free Hill, and its people, and its community in this city. There’s the history of Free Hill. That if Free Hill did exist, Free Hill was a community of vibrant people that loved each other, that cared to each other, that wanted the best for each other, and did everything they could for each other to make them prosperous, successful.

We didn’t get that chance to do that. Because when we went to school, and we were taught to be successful in everything we did, whatever kind of job, whatever experience, or what profession you go in, to be successful. Where we can teach that to our kids about Free Hill because nobody, nothing came out of Free Hill. It’s a one thing. It said, “Can any good thing come out of Free Hill?” The answer is, ‘Yes.” We came out of it. We are now because of our experience in Free Hill and our school’s system. Because I went from the first to level graded Cook, which is all black. I went one year at Mc MIA. And that’s not taking anything from Mc MIA. But my experience at Cook, all Black school, let’s me know. And a lot of people, we had people from Cook, the all Black school that I went, were successful in the military, successful in life, in school, teachers, doctors. That the experience from Free Hill would’ve kept that bloodline going on. That’s what we lost.

In 1971, Vant Hardaway left Athens, Tennessee after finishing undergraduate school. I had told people I will never be back in Athens, Tennessee to live. I’ll say the good Lord by his providence brought me back. When I came back, my mom and dad were still here. I would come in to visit, but then I’d go back out. And then as time went on, when all the siblings had gone, I came back, and I really didn’t expect to come to Athens. I was coming to Cleveland, but I got a position here, and I came on, and did it. I think I’ve continued to work in it, and it made placement. But I was glad to be able to do that because now my parents are, they both transitioned and they’ve passed away. You may hear things with Hammond Cemetery and that’s a cemetery where many black people are buried, but my parents are buried in Memory Gardens in a mausoleum. So, those were some opportunities, and some things that we decided to, my family, my siblings and me, just decided to pursue and to do that. So, it’s a decision of the dead. So, we went to the all Black school, but I enjoyed my time at that school with my friends, and we had our own culture, and our understanding. We didn’t get the best of everything. There’s a historical, and my undergraduate degree was in history in political science. So, I knew the history of segregation, and it was sort of set up by separate but equal. But our world was not equal at all. It was separate, but it was not equal. When we went to the Black school, it was separate and we enjoyed our relationships with our people that we were with. But we didn’t get the best. When a lot of the Civil Rights Act came, and we changed, and started getting some other things, then we got to where we could get some things that we hadn’t been getting. I can remember when we were getting new books, I already had four names or five names in that book. Somebody had got that. So, we got the leftovers. A lot of us, we walked past the school when we went to Cook School, they walked past Forest Hill School, or walked close to Ingleside School and we couldn’t go there. But when the Civil Rights Act passed, then they couldn’t continually do that because the laws were then changing. And the things that were happening with the work of Dr. King and the movement. I think the movement moved some things to Urban Renewal, or the Civil Rights Act began to bring some things to the communities, possibly with some funding and with some monies or doing something. But the people that were making the decisions was not the people that lived by and large in Free Hill because we were not in the main decision making parts of the community. In Athens, Tennessee, most people have their living experiences more equal with others because Athens, Tennessee is not a closed community. It’s not, so you don’t have very many places that you can say is the white community, or the black community, or the Hispanic community. It’s an open community and people just live wherever they want it. Now, the equality of what it would be would depend on what a person’s lifestyle is like; what’s my job?

Xandr Brown: Anna had said that people at Free Hill, they’ve gone on to do, go off to the military, become nurses, become teachers.

Cynthia McCowan: But they wouldn’t do it here though.

Xandr Brown: Right.

Cynthia: The few people that did something, it seems like there was no hope of doing it here. And that’s the sad thing. Your community, because this is beautiful and this town should be booming. It should have gone north and south. Knoxville is an hour north of us. Chattanooga is an hour below us. We should have been encroaching on both of those. You should been going out some, and you’re right on the interstate. So, your industry should have grown, your tourism should have grown. And none of that. Your housing and stuff should have grown. They’ve got some housing that’s starting now and that’s great. But in order to be successful, you have to leave. That shouldn’t exist. It should be optioned, but not, ‘I have to leave.’ It should not be that in order to, ‘I can’t do it here.’ Why can’t you be a doctor here or a lawyer here? Why can’t you be a nurse here? Why do you have to go away to do that? Who’s stopping you from being a lawyer, a doctor, a nurse, police chief, president of a bank here?

The people that took Free Hill, they have to be… if they have a heart, if they have a conscious, they have to know that what they did was wrong. I don’t think they’re okay. Some are, because some are hardcore, but there are some, I believe, who actually feel bad about what happened. And in all of this coming about in us talking and discussing Free Hill, there are so many of the younger Caucasians that did not know what happened. They did not know Free Hill existed to the extent it did. So those that took it that are still alive, they know they did wrong. They don’t care because Tennessee Wesleyan College, when I attended, they now are Tennessee Wesleyan University, but they’re those that don’t care. We got that property for TWU. They don’t care. The YMCA is on Free Hill. My grandparents had their own home. Why did they have to go into an apartment? They had their own property. Why did they have to go into an apartment? That’s because Athens wanted TWU. They wanted the property, so they took it on false pretense. They took it and lied. “We’re going pay you.” But they’ve never been paid. So they owe us. What I would want… Interest over the past 50 years on the value of the property And the value of the property. So you can imagine how much that would be. I would love for them to do what’s right even though our grandparents and our great grandparents are not here to see it. They should want to do right by the residents of Free Hill that are still alive because we’re here, the world needs to know that Free Hill is still alive. They did not destroy us. And I don’t think… They didn’t think we were people. Those were humans that lived on Free Hill. Those were people that had feelings and you just pushed them aside and said… It’s almost like you took a broom and swept them up on a dustpan and just threw them over into the projects. And they had to have planned all of that. Years before my grandparents knew that they were going take their property, they were not given a choice. Had my grandparents been given a choice, had Free Hill been given a choice, everyone would’ve said, “No, we are not moving.”

We can go back now and see different areas of Free Hill that we still recognize. Understand, I can go up now and see places. It’s still familiar. It never leaves. That’s when you lose your history. It’s always there in your mind, your identity, where you came from. It’s always there and it will be there. Which our kids, they won’t experience that because they’ve never seen it. We can tell them about it, explain it to them. But as far as them seeing it with their eyes, your history, it’s your history.

I was pleased when the research was done to say, “We’ll now do a location and a recognition that there was a community called Free Hill.” And that’s what that marker said to me. I remember the day they had the markings… But it was done with the research from a group of students and a teacher had those students and I guess proceeded through leading them through finding, through doing some interviews to maybe looking at a little bit of the geography of it.

But most of those people, and most of us now, very few, know really what Free Hill looked like. It’s not a whole bunch of us not around and those students that did the research to put the marker together over middle school stage students. It had no concept. It’s almost like a lot of kids talk about now when they look at segregation, they don’t know what segregation looks like and most of them don’t want to know. Going back to the markers and being recognized. I mean, dang, Free Hill as a community closed in the middle to late ’60s. And even when they did the research and put the markers up, I don’t think that happened until the ’80s. So 20 plus years. That’s why I felt pleased that someone did the research and said, “Hey, it did exist. It was an entity.”

That’s where we are today. But I do feel that the truth should be told. It needs to be told, the truth needs to be told of where that plaque should be going. On Free Hill, not up here behind a municipal building because that was not Free Hill and nobody really wanted to face the truth. Poor planning and nobody wanted to face the truth. People that I would say that are in charge or whatever, that knew what was going on, they wouldn’t tell that because they wouldn’t look very good. If we really told how TWU had developed here in which you’ve seen it from the Black area. TWU developed a whole lot down there, dorms and you name it. They prospered and other things have too there. Like that daycare center that you saw, they hadn’t been long built in.

It was the biggest free Black community… Just the fact that those were free Blacks. They were never enslaved is something for you to be proud of and that you should want to know. And it affects the rest of this community. Because, there were other pockets of little Black communities here too that don’t get talked about. There’s Shepherdstown in Etowa, there’s Parkstown, there’s Red Hill, there’s Hammer Hill. I think Free Hill would give the rest of this community, if we got to the bottom of it, a true sense of pride. They actually had their own businesses, they had their churches. Eventually they had their own mortuary. They had a small microcosm that had the potential for economic growth. And I think when you learn things like that sometimes it can motivate you to want to achieve. Look what we could have done, let’s go ahead and try doing that. But if you never talk about the beauty of what that community offered and how it was stripped from them, then I think you feel like what we have is what we can have and what we deserve. And there’s no motivating for us to do anything better because you don’t even know anything about the history of how they made that community work in a place that is 90, probably at the time, 95% white and they made it work. It’s something to be proud of. I think they should be motivated by it, but could be wrong. The history’s supposed to be… The truth is supposed to be that they were living there even before the Civil War was over, which would be before 1865. That’s what I’m trying to find. I want to establish that as truth or fiction. One or the other. They say the mid 1800s, that marker says, “Established in the 1850s.” But by whom? That marker doesn’t say by whom. And so you’re missing, that’s information… The text is weak on that marker. It’s not incorrect, I don’t think. But it doesn’t tell you who started it and doesn’t tell you how it ended. When they decided that they really wanted a marker that told their story when they wanted a new marker after we did the Free Hill video series, at the end of that taping, I asked them and that’s not on… Of course, they edited all that. But I said, “What do you want to do? Because, you all seem really upset.” And I was just learning. I was in shock when they were talking about houses burning. I didn’t know any of that until we were taping. And I’m like, “Oh my gosh.” And that marker was in the wrong place. And I’m like, “It is?” And “Yeah, it should be across the street.” So I was like, “What do you want to do?” And they said they wanted to have the marker moved.