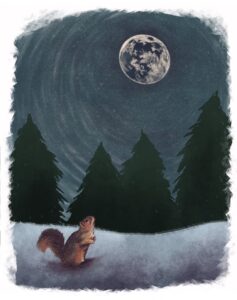

Illustration and story by Nhatt Nichols

It is the season of the dark, and between the discomfort of driving highways at night and the labor of keeping the wood fire alive, it gets easier to choose to stay home and curl up. I always think of this as the story time of year, and this year in particular, I’ve been reading more myths and taking the time to consider how seasons impact the ways that we tell stories.

The stories we tell each other draw us closer. The neighbor you share a story with becomes part of the cultural safety net that builds us into a resilient community, creating the bonds of care that can help support during times of upheaval.

And we are definitely in those times; communities across the country are trying to find ways to feed and house the most vulnerable. This is a time of upheaval, and in difficult times, the connections we forge through narratives are part of what helps us through.

When I reached through my mycillium-like networks to find someone who understands the power of narrative, Craig Howe, the founder and director of the Center for American Indian Research and Native Studies (CAIRNS), was put in my path.

Howe earned a Ph.D. in architecture and anthropology from the University of Michigan, and, amongst so many other things, is the creator and steward of Wingsprings, a retreat and research center he has been designing and building for 22 years on his family cattle ranch in the Lacreek District of Pine Ridge Reservation.

One of my greatest pleasures is having people disagree with my theories. When I told Howe I was writing about Winter as the season of stories, he immediately jumped in to correct me.

“The winter is just part of the year. To me, rural people’s stories, it’s year-round,” Howe said. He went on to explain that narratives, a term he prefers over stories or myth, are important ways rural people navigate relationships and connection at a base level that defies seasonality.

“The question for me as I was going to school was, ‘What is it that differentiates Lakotans from Ojibweans and from Crow and all these other tribes?’ And even in the modern world, people say, well, they have their own language. That’s not it,” Howe said, pointing out that England, Australia and South Africa all share a common language, but not a common culture.

Instead, Howe believes that it’s traditional narratives that define a culture. We spoke a few hours before Waniyetu, the winter moon, became full, which Howe tells me is linked to the story of how the four brothers traveled from the Lakotan underworld and established the four directions.

“That’s how I see these narratives. Take that full moon; talk about it astronomically. So we’re talking about the latest science. We’re not opposing it,” Howe said. “And then, that’s linked to this idea of winter, and winter is linked to these four brothers. That makes it a narrative, a story that’s community specific.”

These narratives that are tied to communities are not just stories in a book; they are living cultural touchstones that help build a sense of identity.

“If I’m talking to someone and I can say, you know, that old guy’s just like Waniyetu or something, right? And then we’re going to understand, oh, some cold, surly dude, right?” Howe explained with a broad smile. “This idea of narrative is not so much to us living human to human, but tying us to this idea of identity as a nation that was here before I was born, it’ll be here way after I’m dead, and that nation and its identity is linked to this land and to these other species here, whether they’re plants or animals.”

Those of us who live all year round in these rural narratives understand the importance of the stories we weave with each other, including those we weave with the nonhuman members of our community. Perhaps I’m wrong about the role of winter in narrative, but at least for me, this is the time of year I’m able to pause, to hear the final croaks of the song frogs, and to spend time sharing the stories that bind my friends and me together.