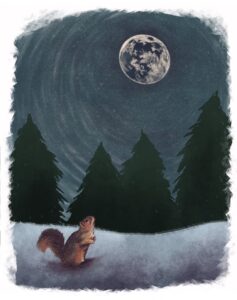

Story and illustration by Nhatt Nichols

Rural places are often depicted as homogeneous, a monolith of food production and outdated ideas. Those of us who live rurally understand how untrue this is and how deeply diverse we are, though many of the same threats to rural stability find their way to each of us across economic, geographic and political divides.

My work took me away from the mossy complexities of the Olympic Peninsula this summer and out to Yuma, Colorado, to work on a project with Prairie Sea Projects and The Nature Conservancy. I traveled through seven Western states, connecting with inspirational rural cultural changemakers along the way. As I wound my way through the west, I found people who were reaching across a multitude of divides to create resiliency among their friends and neighbors. Conversations also circled around disagreements, shadow work, and the nature of living with community conflict.

We are living in incredibly divided times, and finding things we can agree on and amplifying them is the main way I found resilience cultivated. If you can agree on the importance of food production, conservation and joy, then you are more likely to find ways to come together during a crisis.

Driving East to All Points West

From my home in western Washington, I traveled east, staying with nonfiction writer Bryce Andrews and his wife, Gillian, on their cattle farm in Arlee, Montana. Bryce and Gillian are in the delicate balance between ranching and agri-tourism, writing books and raising a family. For Bryce, books and cattle seem to go hand in hoof, and he said that he had an easier time writing after a season focused on the cattle. I’ve experienced that too; sometimes constraints make for more creative lives.

I then headed up to Eureka, Montana, to stay with fellow newspaper editor Nikki Meyer.

In Eureka, Nikki and her neighbors support each other by sharing a barbecue grill, playing piano and singing at each other’s houses. By gathering within their neighborhood, they are creating essential tourist-proof spaces in their small town on the edge of Glacier National Park.

From Eureka, I headed south to the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, where I met Patti and Jason Baldes, a married couple working together to reintroduce buffalo to the prairie and restore the cultural practices of their respective tribes, the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone. Together, they are building resilience quite literally from the ground up: bison play the role of disrupters on the prairie, their sharp hooves scraping the ground and restoring plant diversity to the ecosystem.

The rematriarching of bison to Wind River helps build cultural resilience, too. “The buffalo is intricately tied to our ceremonies, and they were gone for about 130 years,” Jason tells me while we rest next to a Bull Berry Bush on the bison reserve.

Despite that absence, their tribes have held on to the songs and ceremonies, and now their effort to bring buffalo back into the community has created new bonds through food distribution, tribal health, and nutrition programs. “We’re helping to recreate that reciprocal relationship with buffalo that in turn heals us,” Jason said. “They heal the land. They, in turn, heal us. It’s like our long-lost relative is home again. And many folks had forgotten that our relative was gone, but now that our relative is home, there’s a rekindling of that historic relationship.”

Further south in eastern Colorado, Nathan Andrews (no relation to Bryce) raises cattle on the historic Fox Ranch, owned by the Nature Conservancy. Nathan is a sixth-generation cattle rancher with strong ties to the community and the land. Although conservation and cattle may not seem like natural bedfellows, both Bryce in Montana and Nathan in Colorado feel a deep connection to the land and a sense of responsibility to do what is right by it and future generations, particularly in the face of climate instability.

“I was raised with the sense that a lot of people have put in a lot of effort to do the best that they could to raise families and provide for communities here,” Nathan said. “And so in order to honor that, the next generation and the next have to do the best that they can.”

Nathan may have a partnership with the Nature Conservancy and be generationally obligated to do the best by the land that he can, but he also needs to find ways to feed his family. To that end, Fox Ranch is a calf-and-cow operation that provides high-quality grain-finished beef for the commercial market. They run enough cattle to be profitable, moving them frequently to keep the tall grass, which protects prairie chickens from hawks.

It’s a balance: creating environmental and economic stability, raising a family, showing up for your neighbors. You can share a meal or a fenceline with a lot of different kinds of people, and if you’re used to sharing that line, then it’s easier to create a relationship based on reciprocity and care with them.

Going North

I headed north from Colorado to Bison, South Dakota, to visit prairie siren Eliza Blue. We started our conversation by recognizing a kinship in being rural disruptors – we all need to be bison pawing at established ideas in our communities sometimes.

Eliza, a folk singer and sheep farmer, recognizes that a major part of living in rural communities and cultivating deep, genuine resilience is that sometimes you need to shake up ideas and give people the chance to reevaluate their beliefs. Relationships are stronger when we challenge each other, shake out the roots of what we think we understand about our place in the world, and learn how to disagree with each other.

One of the ways each community I visited found resilience was through the creation of third spaces, and Eliza’s Sheep Shed Cafe is one of those magical places that opens up when the need for connection aligns with the seasons. She’s staged poetry readings, concerts and a play there, inviting the kind of resilience you can only form through sharing food, art and big ideas together, creating opportunities to learn to disagree with each other and broaden each other’s minds

It took me five days and thousands of miles to drive home from Bison, hours of staring at horizons and contemplating what all of these people and places have in common in wildly diverse Western landscapes. Although Bison and Yuma aren’t concerned about tourism driving housing prices out of reach, the lack of resources and sustainable economic drivers means they have more in common with Eureka than might appear on the surface.

At each place I visited, I spent time in kitchens and around dining room tables, engaging in conversations about the nature of limited resources and abundance through the different lenses of place. In the rural west, we are able to overcome divisions through a holistic kinship, making space for radical ideas and disagreement while sharing meals and space together.

Nhatt Nichols is a multidisciplinary artist and writer raised on top of a mountain in the Okanogan, Washington State. A graduate of The Royal Drawing School in London, she uses drawing, poetry, and comics to break down political and environmental issues, finding new ways to meet people where they are, and ask them to reach deeper into their ability to care and take action.

Drawing Resilience features interviews with leaders who are doing the hard work of staying in—staying in the work, in relationship, in community, even amid deep divisions, systemic injustices, and social and economic challenges—and inspiring others along the way.

Get this and other rural content in your inbox with the Rural Assembly newsletter.