By Nhatt Nichols

Illustration by Nhatt Nichols

When I tell people that I grew up in a survivalist family, I get a range of reactions and questions, many of which have changed a great deal in the past five years. As more people are impacted by the polycrisis, complex situations where multiple interconnected crises converge and amplify each other, more people are thinking about ways to sustain themselves and the people they love.

Many of us rural folk have to be survivalists to some extent these days. For me, the libertarian survivalist mentality of my youth was a failure; instead, I now look to mutual aid, an organizational model consisting of collaborative exchanges of resources, and community building as the way to prepare for an emergency. And I’m not alone in this.

I spoke with Stephanie Konvicka of Hesed House in Wharton, Texas, and Oceana Sawyer of Nourishing Beloved Community in Washington State about their experiences with disaster preparedness, mutual aid, and the ways they work to strengthen their communities.

Community Building

In Wharton, Texas, Stephanie Konvicka experienced an emergency caused by climate change firsthand. “In 2016, we flooded. Part of our community flooded twice. And then in 2017, we had hurricane Harvey, where 60% of our town flooded, and then it was 2000 homes and half of our county,” Konvicka said.

Konvicka realized that a large part of the devastation came from isolation. She also recognized that creating a space for connection would do more than just support emergency preparedness efforts; it would help create a future in Wharton for young people.

“The actual disasters were the first time I was able to connect the decline in our community to a lack of community resilience, and not just this kind of like, oh, people like to leave a small town and don’t come back,” Konvicka said. “And that wasn’t the case. It was the narrative, but it wasn’t the case.”

Then Konvica got an idea. She had seen a vacant house in a city park and, through the relationships she had built with city staff, asked if she could use the house for yoga and art classes. This would allow local people to process trauma and grow together. And thus, Hesed House of Wharton was born.

“Because it was in a city park, it felt accessible to all community members. A lot of the neighborhoods that typically flood in our community are marginalized neighborhoods that you can drive around and not through. So they felt unseen. They were unseen. Their needs unmet, and all of a sudden, there was something popping up in a park in a neighborhood that is highly vulnerable, and it became this place for everyone,” Konvicka said.

Hesed House is now five houses, all for different types of community programming, including a space for yoga, a community market, and space for meetings.

“It kind of became this thing of, connect to yourself, connect to place, connect to others, and trauma will work itself out for the most part,” Konvicka said.

Mutual Aid

Though the climate is radically different on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State compared to Texas, the need for connection and community is still deeply felt, as the region is overdue for an earthquake and runs a significant tsunami risk.

The nonprofit group Nourishing Beloved Community (NBC) supports People of the Global Majority (PGM), a collective term for people of African, Asian, Indigenous, Latin American, or mixed-heritage backgrounds, who constitute approximately 85 percent of the global population.

Through their food distribution and growing program, they’re building a mutual aid community that can stand up to the challenges of a changing climate.

When Oceana Sawyer, a co-founder of NBC, moved to the Olympic Peninsula, she recognized how mutual aid could provide stronger connections between PGM people in a county that is predominantly White.

“The other point of [mutual aid] is to have people who might be living in the perception of scarcity, poverty or oppression to experience a surplus,” Sawyer said, adding that when she came to the peninsula in 2021, she was surprised by how much PGM folks were focused on reparations from White people. “That’s not how I have existed in the world. As a Black woman, we take care of us,” Sawyer said.

They began with a weekly potluck, bringing people together around a table to talk and make plans together. The next year, they received a grant from the Washington State Department of Agriculture that allowed them to buy food from PGM growers and distribute it to PGM people.

“The idea is as much to feed people as it is to build community,” Sawyer said. “It’s all the same skills you need to navigate a natural disaster. This is the time of the slippery slope; you can see it’s going down, but it’s not going down very fast. So you think you have a little while longer to hang on to your creature comforts, and you don’t.”

Like Hesed House, NBC has remained nimble and responsive to its community with an eye to long-term sustainability. “Our main driver is we really want to encourage our community to have sovereignty around food, have the capacity to grow our own food,” Sawyer said.

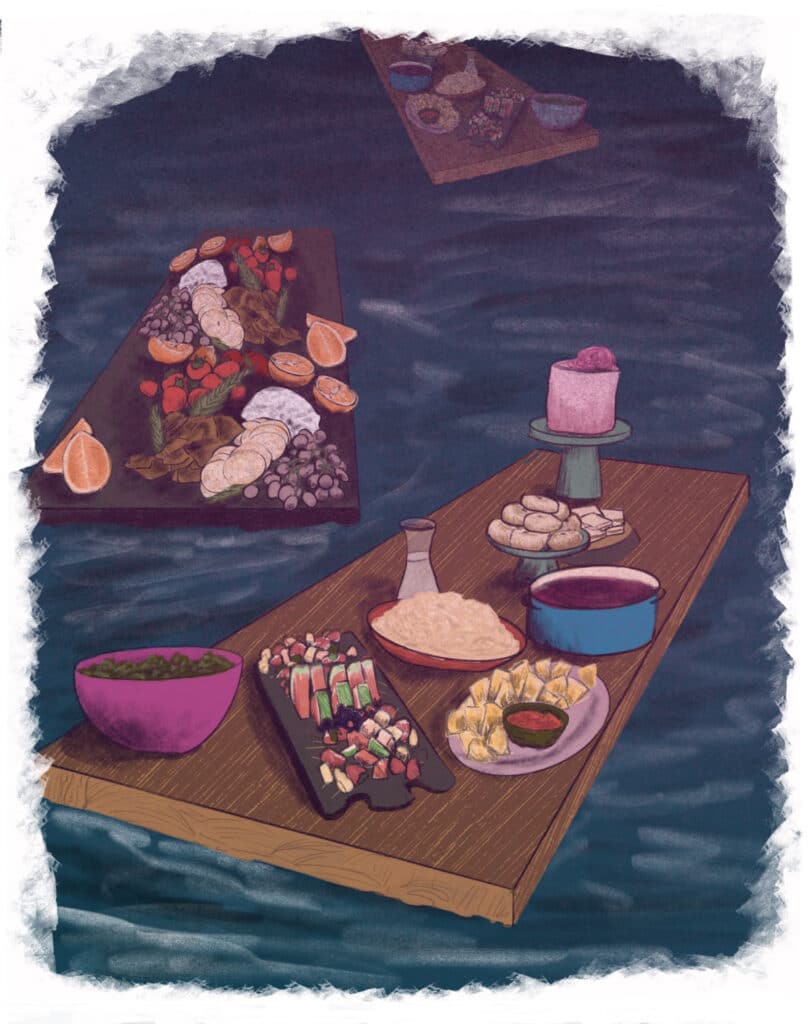

Sawyer recently heard author Dougald Hine speak about the nature of community and mutual aid, and one of his metaphors really stuck with her. “He had an image of a flotilla of tables, these different tables floating together, passing each other.”

It got Sawyer thinking about NBC as just one of those tables. “To me, that is what Beloved Community is. It’s not just Black and brown people; it’s everybody who’s on the same page for life, a flotilla of tables.”