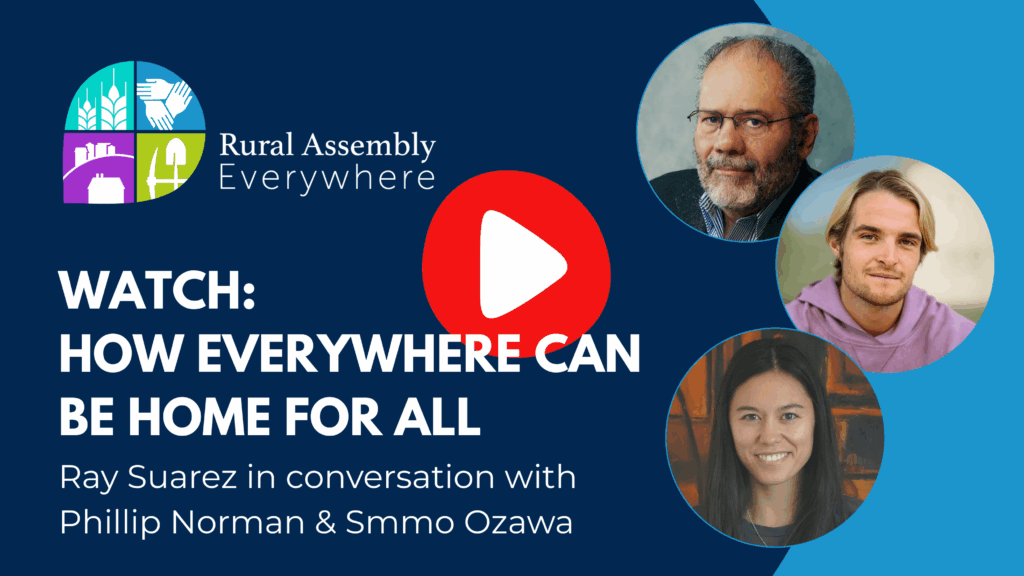

Watch this powerful extended conversation with author, journalist and PBS television host Ray Suarez, a portion of which was originally featured at Rural Assembly Everywhere 2025, our national virtual gathering on Sept. 17.

Rural Assembly Welcoming and Inclusion Fellows Phillip Norman and Smmo Ozawa talk with Suarez about immigration and change in rural America. The conversation explores how immigration is reshaping small towns and rural economies across the country.

“One of the saddest parts of the national conversation around immigration is the belief among a lot of our fellow citizens that this is a zero-sum game —that if someone is getting something, that means there’s less for me,” Suarez said. “To me, that shows a fundamental lack of faith in what America has pulled off pretty successfully for 250 years: the idea of a growing pie, of innovation and forward-looking growth making sure there’s enough for everybody. We’ve sort of lost that faith.”

Ray Suarez

Watch the full conversation on Youtube and find the transcript below.

Transcript

(Edited for clarity)

Phillip Norman:

Hello everyone. I’m Phillip Norman. I’m here with my colleague, Smmo Ozawa, and we’re speaking with longtime broadcaster and journalist Ray Suarez. The title of today’s conversation is How Everywhere Can Be Home for All.

So, Ray, in your recent book We Are Home: Becoming American in the 21st Century, reading that book really informed this podcast that Smmo and I made about immigration in rural America—and your voice is featured on the show. To start off, could you just tell us a little bit about how immigration is reshaping rural America?

Ray Suarez:

Well, you know, Phillip, it is a very old story and a very new one at the same time, which makes it one of the more interesting inquiries in American history right now. Of course, the 19th-century story is very much an immigrant story, but now the 21st-century one is as well.

When the laws were changed in 1965 to reopen America to large immigrant flows, people started to come from different places in the world. What had largely been a coastal and border phenomenon became an everywhere phenomenon. So now immigrants are the backbone, in many places, of the rural economy—the agricultural economy, the small-town economy—in places where there really had never been, or hadn’t been, high levels of immigration in more than a century.

It’s retelling a very old story but with a new twist, because people are coming from different places. They were not used to having Somali immigrants in Minnesota, or Eritreans in Iowa, or Mexicans in communities in the Dakotas. This is a new story and an old one at the same time. And it’s forcing people who are the great-great-great-grandsons and daughters of immigrants to rethink what immigration means.

Smmo Ozawa:

Besides the immigration focus, can you share a story or two from your experiences reporting in rural America about other types of changes you’ve seen in these rural places?

Ray Suarez:

It’s been, in some places, comfortable and really not particularly dramatic—where economic necessity has merged with the readiness of people to dig in and go to work. And in some places, it’s been very tense.

In northeastern Pennsylvania, there’s an old industrial town, Hazleton, which had its glory days earlier in the 20th century. But a lot of the industries that fueled the growth of Hazleton had long since closed. The place was declining in population, census after census. Then people priced out of the New York City real estate market started to move west from the New York metropolitan area and settled in Hazleton—Dominicans, in particular.

This became a political cause for some, who saw an opportunity to capitalize on the discomfort of people with new arrivals who spoke Spanish, who had a different view of what a main street should look like, who wanted to buy houses cheaply and fix them up. And there were some ugly years in Hazleton.

Well, now the city has been growing for two censuses in a row. It’s now roughly 50% Latino, and has a mayor who recognizes that a healthy business community and a healthy, coherent, vibrant economy in Hazleton means embracing rather than shunning the new Dominican population.

Phillip Norman:

Yeah. Another direction we wanted to go in this conversation is beyond the specific focus of immigration. Just as someone who’s reported in rural America, how else have you seen rural America change over the years you’ve been reporting?

Ray Suarez:

There are rural places that have had to struggle with the way marketplaces sort workers, and the way people move around the country. And there are places, like in North Dakota during the fracking boom, where they couldn’t build new housing fast enough. Young men left their families behind to work long stretches, then got a week off to drive a thousand miles home to their wives and kids—but they were making fabulous money extracting oil and gas from places that had been kind of forgotten.

You know, there isn’t one rural American story anymore. There are multiple stories, because different things are happening in different places that force different kinds of changes on people who might have hoped that life would stay stable and predictable over time.

Sudden wealth is changing the nature of places. There are counties in Idaho and Wyoming where wealthy people from far away are building second homes, suddenly demanding an airstrip for private aviation or better roads where people once drove pickup trucks and didn’t mind chip-and-seal roads. But now, if you’re a cop, a teacher, a firefighter, or a nurse, you may be getting priced out of the community where you live—in central Colorado, southern Idaho—by people moving in from the coasts.

That’s what makes America a fascinating, challenging place to cover. It forces us to deal with new challenges all the time.

Smmo Ozawa:

The theme for Everywhere this year is abundance—how the pie is big enough for all of us. Can you share some examples you’ve come across of how storytelling has the power to shift these instincts of scarcity-minded isolation back into attitudes of collaboration and abundance that include rural newcomers?

Ray Suarez:

One of the saddest parts of the national conversation around immigration is the belief among a lot of our fellow citizens that this is a zero-sum game—that if someone is getting something, that means there’s less for me.

To me, that shows a fundamental lack of faith in what America has pulled off pretty successfully for 250 years: the idea of a growing pie, of innovation and forward-looking growth making sure there’s enough for everybody. We’ve sort of lost that faith.

Once you stop believing that this country can provide for all, you can’t believe that newcomers will grow the pie—you just assume they’ll take a piece of yours. But when farms become more productive with a new supply of workers, that doesn’t mean there’s going to be less milk or cheese or higher prices. Over and over again, through American history, immigrants have helped grow the economy and make more for all, even as they fought through suffering and sacrifice.

Whether it was immigrants building the transcontinental railroad, working in the Pittsburgh and Youngstown steel mills, or processing meat in the Chicago stockyards 120 years ago—they’ve always contributed to building this country while finding their own foothold.

Phillip Norman:

In your travels, have you witnessed any turnaround points where people have gone from that zero-sum mindset to a greater acceptance of newcomers’ contributions?

Ray Suarez:

I think if you look at a place like Iowa about 25 or 30 years ago, the governor at the time said, “Look, we have a great public education system, and when Iowa kids finish college, a lot of them leave. They go to Chicago or New York, and they’re not staying here to farm. So we’re going to have to accept people coming from other places.”

And Iowa has become a place that immigrants have gone to. Like I said earlier, this is no longer a coastal or border phenomenon—it’s everywhere. They’ve become part of the fabric of the place.

The next chapter that’s yet to be written is what happens next. I was sitting at a Formica table in a diner in northwestern Iowa, the most Dutch county in America. Successful, productive farms, great lives. I asked a table of farmers, “Are any of your kids staying here to farm?” And they all looked around and said, “No.”

I told them a lot of the work in the county was being done by Mexican and Central American immigrants and asked, “Can you see them owning your farms one day?” They said those men were great workers, they understood farming, but they couldn’t see them owning the farms—it takes too much capital to buy land and equipment today.

And that’s a real problem. It could all end up in the hands of multinational agricultural corporations. People are going to have to decide if that’s really the future they want.

But at the same time, all those farmers understood that the men who had come from other places were now essential to the farming economy—and that’s a good thing.

Smmo Ozawa:

Awesome. Well, thank you, Ray, for speaking with us again. Like I said, your voice was a big help in helping us stitch together the story for our podcast about rural immigration. We appreciate hearing more from you about other aspects of life and the challenges in rural America today.

Ray Suarez:

Thanks for having me. Admitting we need each other is not a bad thing.

Phillip Norman:

Agreed.

Smmo Ozawa:

Agreed.